When your kidneys aren’t working right, what you eat becomes just as important as any medication. A renal diet isn’t about losing weight or eating ‘clean’-it’s about protecting what’s left of your kidney function and avoiding dangerous buildups in your blood. Too much sodium, potassium, or phosphorus can lead to high blood pressure, irregular heartbeat, bone damage, or even heart failure. The good news? With the right knowledge, you can eat well, feel better, and slow down further damage.

Why Sodium Matters More Than You Think

Sodium doesn’t just make food taste salty-it makes your body hold onto water. For someone with kidney disease, that’s a problem. Your kidneys can’t flush out the extra fluid, so it builds up. This raises blood pressure, swells your legs, and puts strain on your heart. The standard advice? Keep sodium under 2,300 mg a day. That’s about one teaspoon of salt. But here’s the catch: most of that sodium isn’t coming from your salt shaker. It’s hiding in packaged foods.A single serving of canned soup can have 800-1,200 mg of sodium. Processed meats, frozen meals, and even bread are loaded. Reading labels isn’t optional-it’s survival. Look for ‘low sodium,’ ‘no salt added,’ or ‘unsalted.’ Avoid anything with ‘sodium’ in the ingredients list: monosodium glutamate (MSG), sodium nitrate, baking soda, or disodium phosphate. These are all sodium in disguise.

Instead of salt, use herbs and spices. Garlic powder, oregano, lemon zest, or Mrs. Dash blends can add flavor without the risk. Cooking at home gives you control. A 2022 CDC study showed that cutting sodium by just 1,000 mg a day can lower systolic blood pressure by 5-6 mmHg in people with kidney disease. That’s the same drop you’d see from some blood pressure meds.

Potassium: The Silent Threat

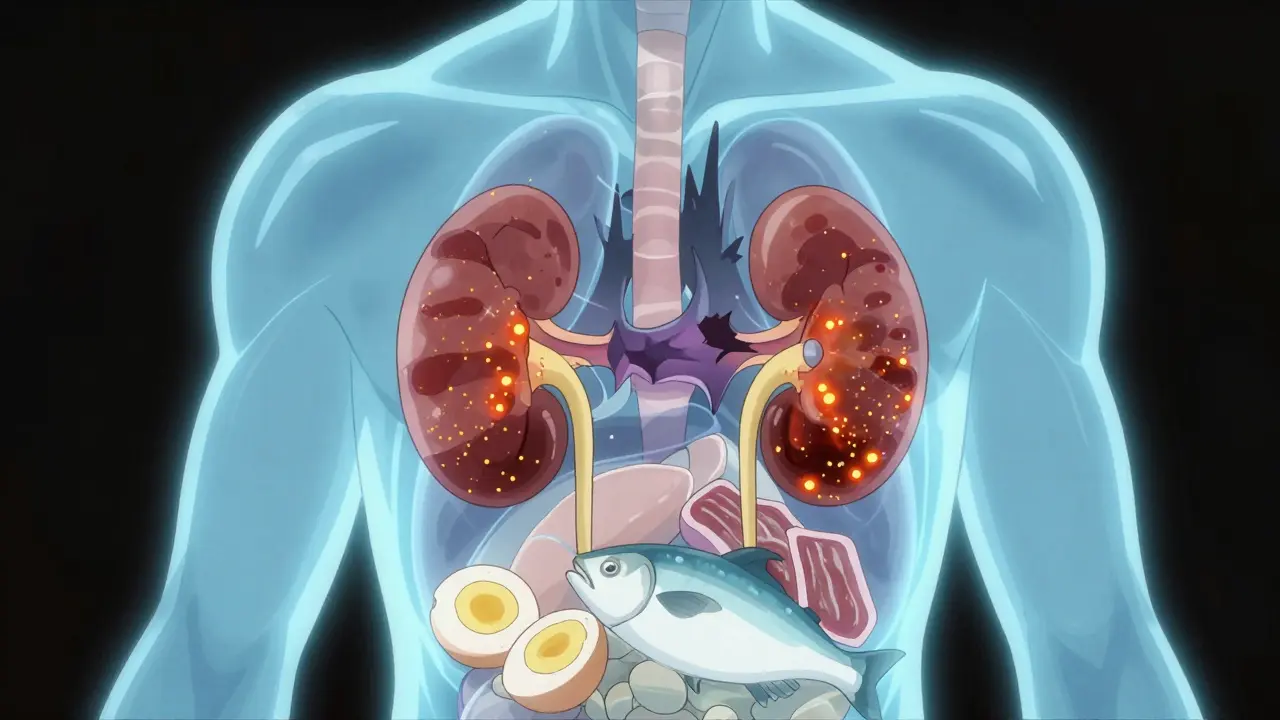

Potassium helps your muscles and heart work right. But when your kidneys fail, it builds up. Levels above 5.5 mEq/L can cause dangerous heart rhythms-sometimes without warning. That’s why many people with stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease need to limit potassium to 2,000-3,000 mg per day.High-potassium foods are often the ones you’re told to eat for good health: bananas (422 mg each), oranges (237 mg), potatoes (926 mg per medium), spinach (839 mg per cup cooked), and tomatoes (400 mg per cup). These need to be swapped out. Choose low-potassium options instead: apples (150 mg), berries (65 mg per ½ cup blueberries), cabbage (12 mg per ½ cup cooked), green beans, and cauliflower.

There’s a trick many dietitians teach: leaching vegetables. Slice potatoes or carrots thin, soak them in warm water for at least 2 hours, then boil them in a large pot of fresh water. This can cut potassium by half. Drain the soaking water-don’t reuse it. This isn’t magic, but it’s science-backed and widely used in renal nutrition programs.

Also, remember this: potassium from animal foods (meat, dairy) is absorbed more easily than from plants. So even if you eat a plant-based diet, you still need to watch portions. A 2023 study in Kidney International Reports found that people who ate more animal protein had higher blood potassium levels, even when their plant intake was high.

Phosphorus: The Hidden Enemy in Processed Foods

Phosphorus is in almost everything you eat. But here’s the twist: your body absorbs natural phosphorus (from meat, dairy, nuts) at about 50-70%. The phosphorus added to processed foods? Up to 90-100%. That’s why colas, processed cheese, deli meats, and frozen pizzas are worse than steak or milk.The goal? Keep daily phosphorus under 800-1,000 mg if you’re not on dialysis. A 12-ounce cola has 450 mg. One slice of processed cheese? 250 mg. A cup of milk? 125 mg. That’s already over half your limit just from drinks and cheese. White bread has 60 mg per slice; whole grain has 150 mg. Choose white over whole grain-not because it’s healthier overall, but because your kidneys can’t handle the extra phosphorus.

Research published in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology in 2022 showed that people who ate more processed foods had 30-50% higher phosphorus absorption, even if their total intake was the same. That’s why dietitians say: avoid ingredients with ‘phos’ in them. Calcium phosphate, sodium phosphate, phosphoric acid-these are all additives. They’re in everything from bread to bottled iced tea.

Some new options are emerging. In 2023, the FDA approved a medical food called Keto-1 that provides protein without the phosphorus burden. And early studies show prebiotic fibers like inulin may reduce phosphorus absorption by 15-20%. These aren’t cures, but they’re tools becoming part of modern care.

Protein: Less Isn’t Always Better

For years, people with kidney disease were told to eat as little protein as possible. That advice has changed. Too little protein leads to muscle loss, weakness, and higher risk of infection-especially in older adults. A 2022 study in the Journal of Renal Nutrition found that restricting protein below 0.6 grams per kilogram of body weight increased malnutrition risk by 34%.Current guidelines from KDOQI recommend 0.55-0.8 grams per kilogram per day. For a 70 kg person, that’s about 38-56 grams of protein daily. Good sources include eggs, fish (salmon, cod, halibut), chicken, and lean pork. Portion size matters: 2-3 ounces of fish, two to three times a week, is plenty. Avoid red meat daily. Plant proteins like tofu and lentils are okay in moderation, but watch potassium and phosphorus levels in those too.

The key is quality, not quantity. High-quality protein gives your body what it needs without overloading your kidneys. It’s a balance-not a restriction.

Fluids, Labels, and Real-Life Adjustments

Many people with advanced kidney disease also need to limit fluids. If you’re producing less than a liter of urine a day, your doctor might tell you to cap fluids at 32 ounces (about 1 liter). That includes water, coffee, tea, soup, ice cream, and even gelatin. Sipping slowly, sucking on ice chips, or using small cups helps.Meal planning takes work. Most people need 3-6 months to get used to the changes. At first, food tastes bland. That’s normal. Over time, your taste buds adjust. You’ll start noticing how much salt is in things you used to love.

Use apps like Kidney Kitchen (downloaded over 250,000 times) to track nutrients. They let you scan barcodes and see sodium, potassium, and phosphorus in real time. Some hospitals now use AI tools that sync with your lab results and adjust recommendations automatically. The Mayo Clinic started piloting one in early 2024.

What About Diabetes and Kidney Disease?

Diabetes causes 44% of new kidney disease cases. That means many people are trying to follow two diets at once: one for blood sugar, one for kidneys. The problem? Heart-healthy foods for diabetics-like bananas, oranges, beans, and sweet potatoes-are often high in potassium and phosphorus.DaVita’s 2023 analysis found that 68% of foods recommended for diabetics fall into the ‘avoid’ or ‘limit’ category for kidney patients. The solution? Work with a renal dietitian. Swap orange juice for apple juice. Pick green beans instead of baked beans. Choose unsweetened almond milk over cow’s milk. It’s not about perfection-it’s about smart choices.

What’s Changing in 2026?

The field of renal nutrition is evolving. In 2023, KDIGO updated its guidelines to say: one-size-fits-all doesn’t work. Your needs depend on your lab results, age, activity level, and how far your disease has progressed. Some European experts now say phosphorus limits below 1,200 mg/day don’t improve survival in non-dialysis patients. The U.S. still recommends 800-1,000 mg, but individualization is the new standard.Research is also looking at the gut-kidney connection. Early trials show certain fibers may help block phosphorus absorption. Genetic testing is being tested in the NIH’s PRIORITY study to predict how your body handles potassium and phosphorus. That could mean personalized diet plans based on your DNA-not just your creatinine level.

The message? Don’t panic. Don’t starve yourself. Don’t follow internet trends. Work with a registered dietitian who specializes in kidney disease. Medicare now covers 3-6 nutrition sessions per year for stage 4 CKD patients because it saves money-up to $12,000 per person annually by delaying dialysis.

Final Thoughts

A renal diet isn’t about giving up food. It’s about choosing better ones. You can still enjoy meals, celebrate holidays, and eat with family. It just takes planning. Start small: read one label a day. Swap one high-potassium fruit for a low-potassium one. Replace soda with water. These steps add up.When your kidneys are struggling, every bite counts. The right diet won’t fix them-but it can give you more time, more energy, and more control over your health.

Reading this felt like a lifeline. I’ve been on a renal diet for 2 years and honestly, the leaching trick for potatoes? Game changer. I used to hate how bland everything tasted-now I use garlic powder, smoked paprika, and a splash of lemon juice. My BP’s stable and I’m not bloated anymore. Small changes, big results.

Also, skip the ‘low-sodium’ canned stuff-it’s still loaded with phosphates. Just cook from scratch. It’s a pain at first, but your heart will thank you.

i just started this diet last month and i’m already noticing less swelling in my ankles. i didn’t know about the soaking trick for veggies-thank you!! i’ve been eating tons of spinach thinking it was ‘healthy’… oops. now i’m swapping to cabbage and green beans. also, i use apple juice instead of orange. small wins, right? 😊

This is so well written. I’m a nurse and I see so many patients overwhelmed by this diet. The part about phosphorus absorption from additives? That’s the one thing no one talks about. My mom’s on dialysis and she used to eat ‘healthy’ whole grain bread-until I showed her the label. 150mg phosphorus per slice. She switched to white and her labs improved in 3 weeks. It’s not about being perfect-it’s about being smart.

While I appreciate the general guidance, this article lacks critical nuance. For instance, the claim that ‘white bread is preferable to whole grain due to phosphorus content’ is misleading without referencing individual glomerular filtration rates. Furthermore, the assertion that ‘potassium from animal foods is more readily absorbed’ is contradicted by recent meta-analyses from the European Renal Association, which found no statistically significant difference in bioavailability between plant- and animal-derived potassium when adjusted for fiber intake. The CDC’s sodium study cited? Small sample size, short duration, no control for medication adherence. This reads like a blog post masquerading as clinical advice.

It’s funny… I used to think ‘renal diet’ meant eating cardboard. Now I see it as a chance to rediscover food. I make cauliflower rice with turmeric and ginger. I roast zucchini with olive oil and rosemary. I even found a recipe for ‘no-salt’ tomato sauce using roasted red peppers and balsamic. It’s not about deprivation-it’s about curiosity. And honestly? My taste buds have gotten so much more sensitive. I can taste the difference in real food now. 🌱❤️

Stop pretending this is just about ‘eating better.’ This is corporate medicine pushing processed ‘renal-friendly’ foods so you’ll keep buying their overpriced ‘medical nutrition’ bars. Who’s behind the FDA’s ‘Keto-1’ approval? Same companies that make the phosphorus-laden processed meats you’re telling people to avoid. You’re not helping-you’re profiting off fear. Real food is cheaper, and you know it.

Okay, but what if you’re on a fixed income? I work two jobs and don’t have time to soak potatoes for two hours. And ‘read labels’? Try reading them when you’re on Medicaid and the only thing available at the food pantry is canned chicken and salted beans. This advice is for people who can afford to cook from scratch and have a dietitian on speed dial. For the rest of us? We just survive.

Phosphorus additives are the real villain. And yes, colas are worse than steak. I quit soda. My P level dropped 2 points in a month. No meds changed. Just stopped drinking the poison.

They’re lying about potassium. The real danger isn’t bananas-it’s the government’s push to replace salt with potassium chloride in processed foods. That’s why your levels are spiking. They want you dependent on meds. The FDA banned potassium iodide in salt… but not potassium chloride. Coincidence? I think not. Also, dialysis centers profit when you’re high in potassium. They charge more for emergency treatments. Think about it.

Look, I’ve been doing this for 7 years. I don’t care what the ‘guidelines’ say. I eat what I want. I take my meds. I get my labs checked. If my potassium’s high, I drink some water. If my phosphorus is up, I skip cheese for a week. You don’t need a PhD to live with kidney disease-you need common sense and a good doctor. Stop turning this into a religion. Food is meant to be enjoyed. I eat a burger once a week. I live. You try it.

I’m so tired of people acting like this diet is ‘empowering.’ My husband died because he followed this advice too strictly. He lost 40 pounds in 6 months. No muscle. No strength. Just… gone. They told him to eat ‘low protein’ and now he’s in the ground. Who’s responsible for that? The dietitians? The doctors? The article? This isn’t ‘control’-it’s slow starvation dressed up as care.

Hey everyone-this is my third year on this diet and I’m still here. I’m 68. I walk 3 miles a day. I cook for my grandkids. I use the Kidney Kitchen app every Sunday to plan meals. I swap out one thing a week. Last week: I replaced my morning orange with a pear. This week: I’m trying almond milk. You don’t have to do it all at once. Start with one label. One swap. One day. You’re not alone. We’re all learning together. And you’re doing better than you think.

My abuela used to say: ‘La comida es amor.’ Food is love. So I make her sofrito with low-sodium tomatoes, garlic, and a pinch of cumin. I serve it with white rice and fried plantains (soaked first, of course). My nephews think it’s the best thing ever. Who says kidney diet = boring? We’re not giving up flavor-we’re reinventing it. 🌶️❤️

Why are we letting the FDA and Big Pharma dictate what we eat? In India, they eat lentils and spices and have low kidney disease rates. Here? We’re poisoned by processed food and told to ‘eat clean.’ Meanwhile, the same companies that make the phosphates are funding these ‘guidelines.’ This isn’t medicine-it’s marketing. And you’re falling for it.

I’ve been managing CKD for 5 years now, and I’m from India, so I’ve seen both worlds. In India, we use a lot of turmeric, coriander, cumin, and fenugreek-natural anti-inflammatories. We don’t have ‘renal diet’ labels, but we’ve been doing this for centuries. Boil dal with minimal salt, use rice instead of wheat, avoid processed snacks. And guess what? Our elderly have lower rates of kidney failure. The problem isn’t the diet-it’s the industrialization of food. We need to go back to roots, not buy ‘medical foods.’ Also, soak your rice overnight-it reduces phosphorus too. Who knew? 🙃