What if you could know, before taking a pill, whether it would help you-or hurt you? That’s not science fiction. It’s pharmacogenomics testing, and it’s already changing how doctors choose medications for millions of people.

Every year, over 100,000 Americans die from reactions to drugs that were supposed to help them. Many of these reactions aren’t random. They’re written in your DNA. Your genes control how your body breaks down medicines. Two people can take the same antidepressant at the same dose, but one feels better while the other gets dizzy, nauseous, or worse. That’s not bad luck. It’s biology.

How Your Genes Talk to Your Medications

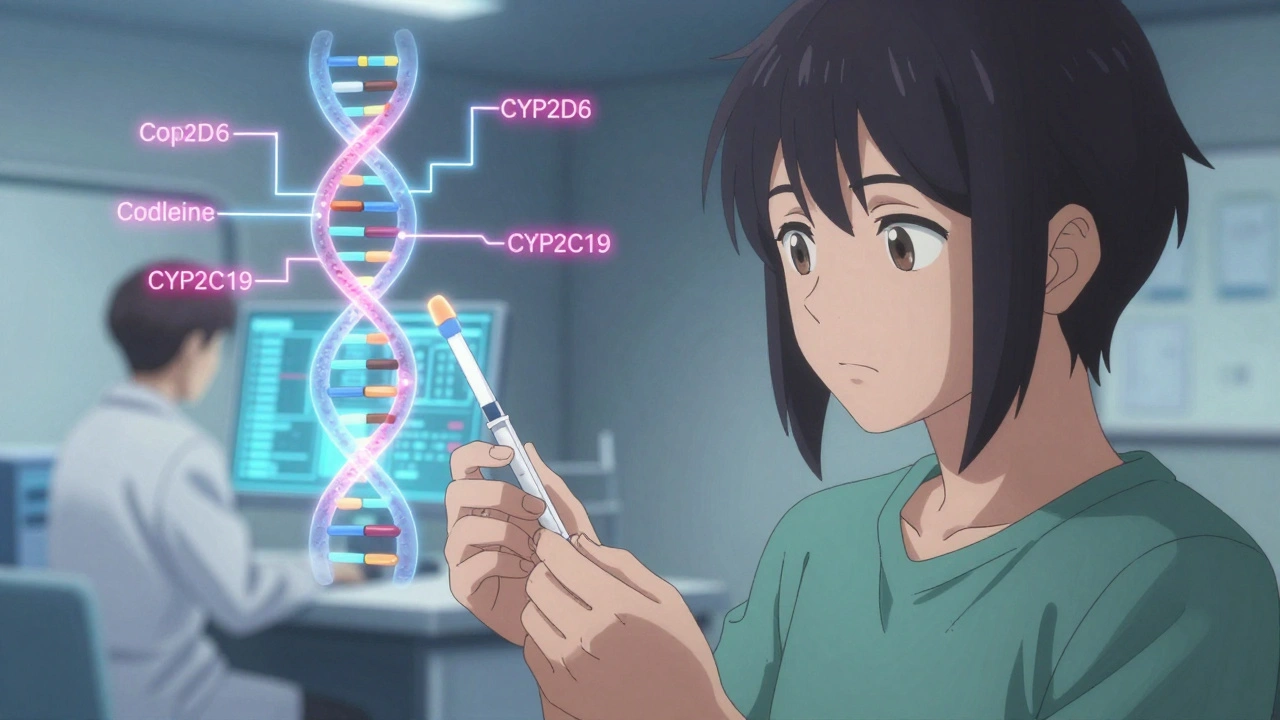

Your body uses enzymes to process drugs. The most important ones are made by genes like CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9. These are part of the cytochrome P450 family, and they handle about 75% of all prescription medications. If your version of CYP2D6 is slow, you might not break down codeine or tramadol properly-meaning you get no pain relief, or worse, toxic buildup. If you’re a fast metabolizer, your antidepressant might vanish from your system before it can work.

Pharmacogenomics testing looks at these genes using a simple saliva swab or blood sample. The results tell your doctor whether you’re a poor, intermediate, normal, rapid, or ultra-rapid metabolizer for each key enzyme. That’s not guesswork. It’s science backed by over 100 clinically proven gene-drug pairs. For example, the HIV drug abacavir can cause a deadly allergic reaction in people with the HLA-B*57:01 gene variant. Testing for this variant before prescribing has cut those reactions to almost zero.

Where It’s Already Making a Difference

Some fields are leading the way. In mental health, where up to 60% of patients don’t respond to their first antidepressant, pharmacogenomics is changing outcomes. A 2022 study found that patients who got gene-guided treatment were 30.5% more likely to go into remission than those on standard care. One patient in Sydney told me, after five failed antidepressants, her test showed she was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Switching to bupropion-drugs that don’t rely on that enzyme-gave her relief within weeks.

In heart disease, the blood thinner clopidogrel (Plavix) doesn’t work well in 25-30% of people because of a CYP2C19 variant. Without testing, they’re at high risk for another heart attack. But if you know you’re a poor metabolizer, your doctor can switch you to ticagrelor or prasugrel-drugs that work regardless of your genes. The FDA reports a 50% drop in major cardiac events when this switch happens.

In cancer, drugs like tamoxifen for breast cancer need CYP2D6 to become active. If you’re a poor metabolizer, tamoxifen may not work at all. Testing lets oncologists choose alternatives upfront, avoiding months of ineffective treatment.

What the Test Can’t Do

Pharmacogenomics isn’t magic. It doesn’t explain everything. Studies show genes account for only 10-15% of why people respond differently to most drugs. The rest? Age, diet, liver function, other medications, even gut bacteria. A gene test won’t help you if you’re taking a drug like penicillin-its effects don’t vary much by genetics. It also won’t predict side effects like weight gain or sexual dysfunction, which aren’t tied to metabolism genes.

And not all gene variants are well understood. Most research has been done on people of European descent. For other populations, the data is thin or missing. That’s a major gap. A test might say you’re “normal” for CYP2D6-but if your ancestry isn’t in the database, that label could be wrong.

Testing Options and Costs

There are three main types of tests:

- Targeted panels (most common): Test 5-15 key genes for 50-100 drugs. Cost: $250-$500. Used in clinics like OneOme, Invitae, and Genelex.

- Whole exome sequencing: Looks at all protein-coding genes. Cost: $500-$1,000. Often used in research.

- Whole genome sequencing: Reads your entire DNA. Cost: $1,000-$2,000. Overkill for most drug decisions right now.

Most doctors use targeted panels. They’re accurate, affordable, and focused on drugs you’re likely to take. Results come back in 3-14 days. If your doctor is set up for it, the report will come with clear recommendations: “Use drug X instead of drug Y,” or “Reduce dose by 50%.”

Medicare Part B covers testing for certain drugs like clopidogrel and abacavir. Private insurance? Only about 35% of plans cover it. That’s the biggest barrier. Many patients pay out of pocket-$400 is a lot if your insurer won’t help.

Why Your Doctor Might Not Use It

Even if you get tested, your doctor might not know what to do with the results. A 2022 survey found only 15% of physicians feel confident interpreting pharmacogenomic reports. Many don’t know where to find the guidelines. That’s changing. EHR systems like Epic now auto-flag dangerous drug-gene interactions. If you’re on a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer and your doctor tries to prescribe codeine, the system pops up: “High risk. Consider alternative.”

Pharmacists are stepping in. In academic hospitals, 72% now have pharmacogenomics-trained pharmacists who review test results and advise prescribers. But in small clinics? Still rare. If you want this service, bring your report. Ask: “Does this change what I’m taking?” Don’t assume your doctor knows.

The Big Picture: Where This Is Headed

Right now, fewer than 5% of prescriptions use pharmacogenomic data. But that’s growing fast. In 2023, 18.3 million tests were done in the U.S.-up from 2.1 million in 2017. The FDA now includes pharmacogenomic info in the labels of 178 drugs. By 2027, experts predict 30% of prescriptions will be guided by genes.

The future? Pre-emptive testing. Imagine getting your DNA profile done once in your 20s or 30s, stored in your medical record, and used every time you get a new prescription. That’s happening at places like the University of Florida and the NIH’s All of Us program, which has already sequenced over 620,000 people. By 2030, half of all U.S. adults could have their pharmacogenomic data on file.

The savings? The Rand Corporation estimates $137 billion a year in the U.S. alone-fewer hospitalizations, fewer failed treatments, less trial and error. That’s not just money. It’s time, pain, and lives saved.

What You Can Do Today

If you’ve tried multiple medications without success-especially for depression, anxiety, chronic pain, or heart disease-ask your doctor about pharmacogenomics testing. Bring up specific drugs you’ve taken and how they affected you. Say: “I’ve had bad reactions or no results with several meds. Could my genes be playing a role?”

Don’t wait for your doctor to bring it up. Most still don’t. But you can be the one to ask. If your insurer won’t cover it, consider paying out of pocket. A $400 test could save you months-or years-of trial and error.

And if you’re on a drug with a known genetic warning-like abacavir, clopidogrel, or warfarin-ask if you’ve been tested. If not, request it. It’s not optional anymore. It’s standard care.

Pharmacogenomics isn’t about predicting your future. It’s about making your present treatment work-so you don’t have to keep guessing what’s right for your body.

Is pharmacogenomics testing covered by insurance?

Medicare Part B covers testing for specific drugs like clopidogrel and abacavir when medically necessary. Private insurance coverage is patchy-only about 35% of plans pay for it. Most commercial insurers require prior authorization and limit coverage to certain conditions, like treatment-resistant depression or heart disease. Always check with your insurer before testing.

How accurate are pharmacogenomics tests?

The tests themselves are highly accurate-over 99% for detecting known gene variants. But accuracy doesn’t mean certainty. A test tells you how your body *might* process a drug, not how it *will*. Other factors like age, liver health, and other medications also matter. The guidelines from CPIC and DPWG are based on strong clinical evidence, but they’re not foolproof. They’re tools to guide decisions, not replace clinical judgment.

Can I get tested without a doctor’s order?

Some direct-to-consumer companies offer pharmacogenomic tests online, but they’re not regulated for clinical use. Results from these tests may not be accurate or actionable in a medical setting. For reliable, clinically validated results, you need a test ordered by a licensed provider and processed in a CLIA-certified lab. Your doctor can order it, or you can use a service like OneOme or Invitae that works with providers.

Does pharmacogenomics testing replace therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM)?

No. They’re different tools. TDM measures the actual drug level in your blood-useful for drugs like lithium or vancomycin where levels must stay in a narrow range. Pharmacogenomics predicts how you’ll metabolize a drug before you even take it. TDM needs repeated blood draws; pharmacogenomics is a one-time test. Many doctors use both: genes to choose the right drug, TDM to fine-tune the dose.

How long do the results last?

Your genes don’t change. Once you’ve been tested, your pharmacogenomic profile is valid for life. You only need to do it once. The results can be added to your medical record and used for every new prescription. That’s why pre-emptive testing is becoming the goal-get it done once, benefit for decades.

Are there risks to getting tested?

The physical risk is zero-it’s just a saliva swab or blood draw. The bigger risks are psychological and practical. Some people worry about genetic discrimination, but GINA (the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act) protects against health insurance and employment discrimination in the U.S. The real issue is misunderstanding results. A test won’t tell you which drug is perfect-it tells you which ones to avoid or adjust. Don’t expect miracles. Expect better-informed choices.

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me my grandma’s 30-year struggle with SSRIs was just her DNA being a stubborn bastard? I’ve been calling it ‘bad luck’ my whole life. Turns out my genes were just trolling me. 😅

From a clinical pharmacogenomics standpoint, the CYP450 polymorphisms are indeed the most clinically actionable variants-especially CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. But the real bottleneck isn’t the science, it’s the EHR integration and provider literacy. We’ve had the data since 2004; we just haven’t built the infrastructure to act on it. CPIC guidelines are solid, but most PCPs still don’t know how to access them. 🤔

It’s wild to think that we still prescribe meds like we’re throwing darts blindfolded. I mean, we map galaxies but we don’t know how your body will react to a simple pill? This isn’t just medicine-it’s justice. People shouldn’t have to suffer through five antidepressants because their doctor didn’t check a gene. It’s 2025. We’ve got the tech. Use it.

And yeah, the cost sucks-but imagine the cost of *not* doing it. ER visits. Suicides. Lost years. A $400 test is a bargain when it saves a life. I wish this was standard before you even get your first prescription.

Also, the ancestry gap? Yeah. That’s not just a gap-it’s a canyon. My cousin in Lagos got prescribed clopidogrel and had a stroke. No one even thought to test. We’re leaving entire continents behind. This isn’t science-it’s colonialism with a lab coat.

Let’s not make pharmacogenomics a luxury for the rich and white. Let’s make it a human right.

Who is paying for this? The government? Big Pharma? I’m just saying-if your genes determine whether a drug works, then maybe your genes are being used to sell you more drugs. I’ve seen this before. They test you, then they upsell you on the ‘better’ drug. It’s not medicine-it’s marketing.

Bro. I got tested. Turned out I’m a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer. My Adderall vanished like it was never there. Switched to Vyvanse. Life changed. 🚀

The real elephant in the room isn’t the test-it’s the fact that we’ve outsourced clinical judgment to algorithmic flags in Epic. Your doctor doesn’t think anymore; they just click ‘approve alternative’. Pharmacogenomics isn’t empowering medicine-it’s automating compliance. We’re turning doctors into data-entry clerks with stethoscopes.

And don’t get me started on the ‘one-time test’ myth. Genes don’t change, but epigenetics do. Your environment, stress, microbiome-all of it modulates expression. This isn’t destiny. It’s a starting point. But no one wants to admit that.

Wait… so if my genes say I can’t metabolize a drug, but I still take it and survive… does that mean the test is wrong? Or is Big Pharma hiding the truth? I’ve been on 7 different antidepressants. All worked… kinda. But now they want me to pay $400 to be told what I already know? I think this is a scam. 🚩

Genes? Pfft. In India, we just use Ayurveda and pray. If your body can’t handle a pill, maybe you’re just spiritually blocked? I tested my cousin’s DNA-he was ‘poor metabolizer’ for everything. He took turmeric, yoga, and a mantra. Now he’s fine. No drugs needed. Science is just a Western religion anyway.

This is beautiful. But let’s not forget: in Lagos, a man with a CYP2C19 variant died because the hospital didn’t have the test. Not because he couldn’t afford it-because it didn’t exist there. We need global equity, not just American convenience. Pharmacogenomics must be a global public good-not a boutique service for the privileged. If we’re going to map genes, we must map access too.

And yes, I’ve seen the data. The 10–15% genetic contribution? That’s still 10–15% more than we had yesterday. We don’t need perfection-we need progress. Start with what we have. Build from there.

Let’s not wait for the perfect system. Let’s build the imperfect one-and fix it as we go.

My doc ordered the test after I told her I’d been on 4 SSRIs and still cried every morning. Turned out I was a slow metabolizer. Switched to bupropion. First week: I laughed. Like, actually laughed. No joke. I forgot what that felt like.

Worth every penny. Just ask.