When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $1,200 bill for a month’s supply of a diabetes drug, it’s easy to assume that’s what everyone pays. But that’s not true. In Japan, the same drug costs about $50. In France, it’s $80. In Canada, it’s $150. Why such a wild difference? The answer isn’t about how drugs are made. It’s about how countries decide what to pay for them.

Why the U.S. Looks So Different

The U.S. doesn’t have a national drug price system. Instead, prices are set through private negotiations between drug makers and insurers, pharmacies, and pharmacy benefit managers. That means there’s no single price - there are list prices, net prices after rebates, and prices for Medicare, Medicaid, and private plans. And most of the time, what you see on the shelf is the list price - the highest one.Here’s the twist: brand-name drugs in the U.S. cost, on average, 4.2 times more than in other wealthy countries. For drugs like Ozempic, Eliquis, or Xarelto, the gap is even wider. Medicare’s newly negotiated price for Jardiance in 2025 is $204 - still nearly four times what Japan pays. But here’s what most people miss: generic drugs in the U.S. are 33% cheaper than the global average. That’s because the U.S. has a massive generic market - 90% of all prescriptions are for generics. That’s not true anywhere else. In Germany or France, generics make up less than half of prescriptions.

This creates a split system. Americans pay way more for new drugs, but way less for old ones. That’s why some economists say the U.S. system is "efficient" - it keeps innovation going by letting companies charge high prices for new drugs, while using cheap generics to keep overall spending down. But for the person who needs a new drug, that efficiency doesn’t help.

How Other Countries Control Prices

Most developed countries don’t rely on markets to set drug prices. They use one of three tools: price controls, reference pricing, or direct negotiation.Japan and France use strict price controls. The government sets a maximum price for every drug, and if the company doesn’t agree, the drug doesn’t get covered. Japan renegotiates prices every two years. That’s why Jardiance, Entresto, and Imbruvica are cheapest there. They’ve been negotiating down prices for over a decade.

Germany and Canada use reference pricing. They pick a few similar drugs and set the price based on the cheapest one. If a new drug costs more, the patient pays the difference. Canada does this nationally. Germany does it by drug class. That’s why you’ll often see Germany and Canada with higher prices than Japan - they’re not as aggressive in forcing cuts.

Australia and the United Kingdom combine both. They negotiate directly with drug makers and use international prices as a benchmark. Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) often ends up with the lowest prices for drugs like Eliquis and Xarelto because they’re willing to walk away from a deal.

The Medicare Negotiation Shift

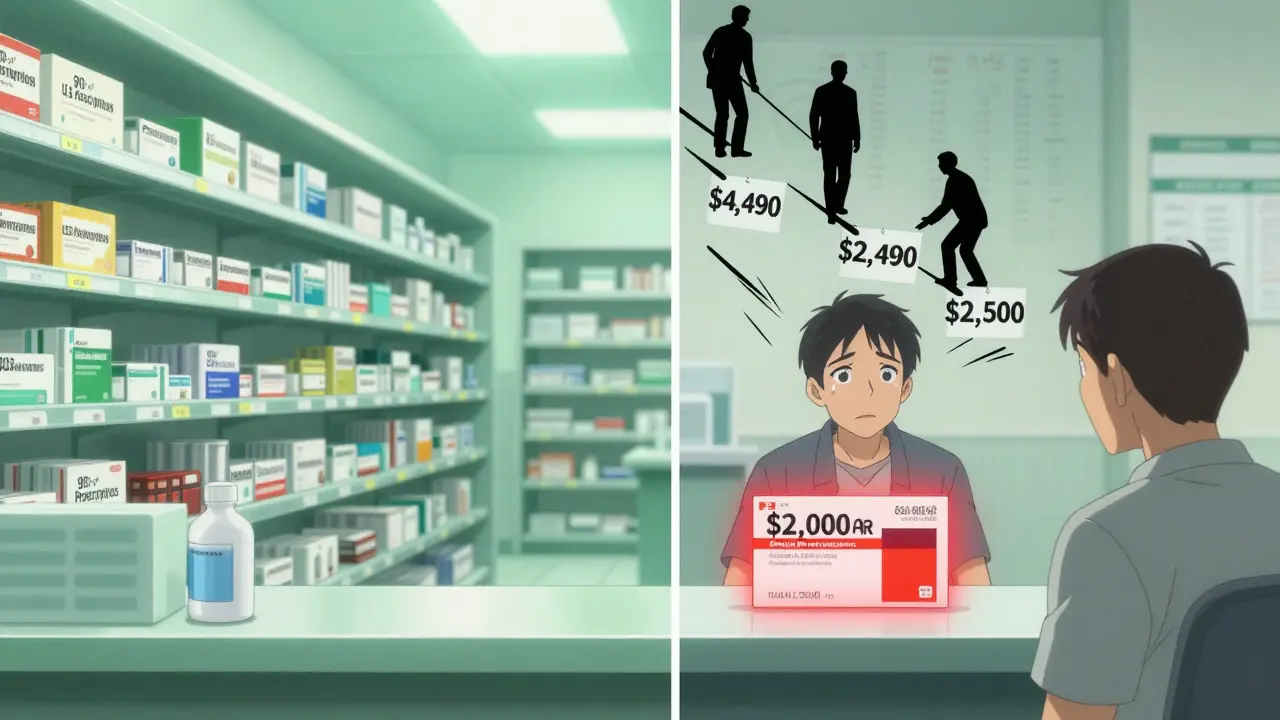

Until 2022, Medicare wasn’t allowed to negotiate drug prices at all. It had to pay whatever the manufacturer asked. That changed with the Inflation Reduction Act. In 2023, Medicare picked 10 high-cost drugs for its first round of negotiations. The results? Prices dropped by 40-70% for those drugs - but they’re still 2.8 times higher than what other countries pay on average.For example, Stelara’s Medicare price is $4,490. In the UK, it’s $2,822. In Germany, it’s $2,910. In Japan, it’s $2,200. So even after negotiation, the U.S. is still paying more. That’s because Medicare’s starting point was the U.S. list price - not the global price. The negotiation didn’t reset the system. It just lowered it a bit.

By February 2025, Medicare will announce its next 10 drugs for negotiation. Experts expect drugs like Humira, Dupixent, and Revlimid to be next. But even if prices drop 50%, they’ll still be higher than in most other countries.

Global Price Disparities Go Beyond the OECD

Most comparisons focus on rich countries. But when you look at 72 countries - including low- and middle-income ones - the picture gets even wilder.A 2024 study in JAMA Health Forum found that in Lebanon, essential medicines cost just 18% of what they do in Germany. In Argentina, they cost 5.8 times more. Why? In Lebanon, medicines are often imported secondhand or smuggled. In Argentina, currency instability and import restrictions make drugs scarce and expensive.

Regionally, the Americas have the highest median prices - 165% of Germany’s baseline. Europe is lower at 138%. The Western Pacific (including Australia, Japan, South Korea) is the cheapest at 132%. That’s not because those countries are poorer. It’s because they’ve built systems that force prices down.

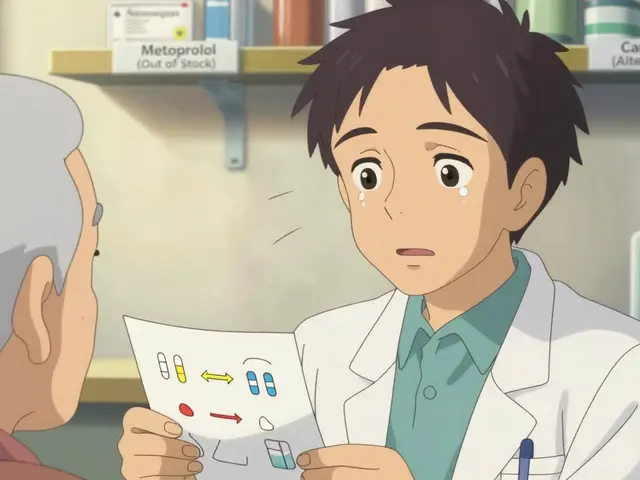

Why It Matters - Beyond the Bill

High drug prices aren’t just about cost. They affect access. In the U.S., 1 in 4 adults report skipping doses or not filling prescriptions because of cost. In countries with price controls, that number is below 5%.It also affects innovation. The U.S. funds a huge share of global drug research - about 45% of all R&D spending. Companies say they need high U.S. prices to pay for risky research. But studies show that most breakthrough drugs are developed in public labs (like NIH) or funded by public grants. The U.S. pays more, but doesn’t get more drugs. It just gets them earlier - and at a higher price.

Meanwhile, countries like China and India have become major players in generic manufacturing. China’s national drug negotiations have cut prices for cancer drugs by up to 80%. India exports 20% of the world’s generic medicines. They’re not waiting for the U.S. to change. They’re building their own systems.

What the Data Really Shows

There’s no single reason drug prices vary. It’s not about R&D costs. It’s not about taxes. It’s about policy.- U.S. list prices for brand-name drugs are the highest in the world - by a lot.

- U.S. generic prices are among the lowest - because of market size and competition.

- Medicare negotiations are a step toward fairness, but they’re still based on U.S. list prices, not global ones.

- Countries that negotiate directly or use reference pricing consistently get lower prices.

- Price controls don’t kill innovation - they just shift how companies make money.

The myth that high U.S. prices fund global innovation is just that - a myth. The U.S. doesn’t pay more because drugs are more expensive to make. It pays more because it’s the only country that lets drugmakers set prices without limits.

For patients, that means two things: If you need a generic, you’re getting a great deal. If you need a new drug - you’re paying the highest price on Earth.

Why are drug prices so much higher in the U.S. than in other countries?

The U.S. doesn’t regulate drug prices. Unlike most countries that use price controls, reference pricing, or direct negotiation, the U.S. lets drugmakers set list prices freely. Medicare couldn’t negotiate until 2022, and even now, it’s limited to a small number of drugs. Private insurers negotiate too, but they often accept high prices to keep drugs on their formularies. The result? List prices are inflated - especially for brand-name drugs.

Do U.S. drug companies make more profit because prices are higher?

Not necessarily. While U.S. list prices are higher, many drugs are sold at a discount after rebates. Drugmakers often give large rebates to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers to get their drugs on coverage lists. That means net revenue - what they actually keep - is much lower than the list price. Still, because the U.S. market is so large, companies can afford to charge high list prices knowing they’ll get some of it back.

Are generic drugs cheaper in the U.S. because they’re lower quality?

No. Generic drugs in the U.S. must meet the same FDA standards as brand-name drugs. They contain the same active ingredients, dosage, and effectiveness. The reason they’re cheaper is because of competition. Dozens of companies can make the same generic, so prices drop. In countries with fewer generic manufacturers or stricter approval rules, prices stay higher.

Why does Japan have the lowest drug prices?

Japan uses strict, government-set price controls and renegotiates drug prices every two years. If a drug is too expensive, the government lowers the price - sometimes by over 50%. They also use international reference pricing, meaning they look at prices in other countries and set their own below the average. This keeps prices low for both brand-name and generic drugs.

Will Medicare negotiations lower drug prices for everyone?

Only for Medicare Part D beneficiaries - about 65 million people. Other insurers aren’t required to match Medicare’s negotiated prices. But in practice, many private insurers do, because they use Medicare’s price as a benchmark. So while the change is limited at first, it’s likely to ripple through the system over time.

Do high U.S. drug prices fund global medical innovation?

It’s a common argument, but evidence doesn’t back it up. Most breakthrough drugs are developed in public labs or with public funding. Companies then license them and charge high prices in the U.S. to recoup costs. But studies show that countries with lower prices - like Germany or Japan - still get new drugs just as fast. Innovation isn’t tied to high U.S. prices - it’s tied to research investment, which the U.S. already leads in.

This is why the system is broken. No one in their right mind would pay $1200 for a pill when Japan pays $50. It's not about innovation. It's about greed. And the fact that Medicare only just started negotiating? Too little, too late. We're literally subsidizing drug companies while people skip doses. This isn't healthcare. It's a casino.

I really appreciate how this breaks down the difference between brand-name and generic prices. I didn't realize U.S. generics are cheaper globally. My mom takes metformin and pays $4 at Walmart. She has no idea how lucky she is. Meanwhile, my cousin in Canada pays $150 for the same brand-name drug. It's not fair, but it's also not as simple as 'America bad'. There's a weird balance here.

The whole 'U.S. funds global innovation' argument is just a PR stunt. Companies don't invent drugs in garages. NIH and public universities do. Then they slap a $1000 price tag on it because they can. And no one calls them out. Meanwhile, the rest of the world just says 'nope' and negotiates. It's not complicated. It's corporate cowardice wrapped in a lab coat.

It is imperative to recognize that the structural disparities in pharmaceutical pricing are not indicative of inefficiency per se, but rather a reflection of divergent policy frameworks. The United States operates within a market-based paradigm, whereas most OECD nations employ centralized, administrative pricing mechanisms. The consequence of this divergence is not necessarily suboptimal outcomes, but rather a reallocation of financial burden. One must also acknowledge the role of the FDA in ensuring therapeutic equivalence of generics, which contributes to their cost-effectiveness.

Let me guess - the next thing they’ll say is that we need to ‘reform’ Medicare instead of just capping prices. Or maybe they’ll blame China. Or India. Or the ‘greedy pharma CEOs’. Funny how no one ever says ‘maybe the whole system is rigged’. The same people who scream about socialism when it’s for vaccines are fine with it when it’s for private jets. This isn’t about cost. It’s about control. And they’re winning.

The economic architecture of pharmaceutical pricing in the Global North is fundamentally a rent-seeking mechanism predicated on intellectual property monopolies. The U.S. model exemplifies neoliberal capture, wherein regulatory capture by PBMs and insurer oligopolies distorts price discovery. Meanwhile, emerging economies like India and China are reconfiguring global supply chains through state-backed generic manufacturing - a form of asymmetric economic warfare against Western IP hegemony. The data is clear: price controls are not anti-innovation; they are pro-equity.

You know who’s really behind this? The shadowy network of pharmacy benefit managers. They’re the ones who negotiate rebates, then hide the real price. The drug companies? They’re just playing along. The government? They’re asleep. And we’re the ones getting screwed. I read somewhere that PBMs made $50 billion last year off this mess. $50 BILLION. And we’re supposed to believe this is about ‘innovation’? No. This is a Ponzi scheme with syringes.

I work in a clinic. I see it every day. People choosing between insulin and rent. I’ve had patients cry because they’re splitting pills to make them last. No one should have to do that. This isn’t politics. It’s human. We’re not talking about profits. We’re talking about lives.

I think it’s important to recognize that while the U.S. system is broken for brand-name drugs, the existence of a robust generic market is actually a strength. It means we have access to affordable, life-saving medications for millions. The problem isn’t the generics - it’s the lack of price transparency and negotiation for new drugs. We don’t need to scrap the system. We need to fix the parts that are broken. And Medicare’s negotiation is a start.

I am from India and we make 20% of the world's generic drugs. We export to Africa, Latin America, even Europe. Our factories produce medicines at 1/10th the cost. But here in US, people still pay 10x because they dont know. Why? Because pharma companies want to keep profits. I am proud of our country. We dont need to charge high prices to innovate. We innovate by making affordable. And yes, we do it better than US. US is stuck in old ways. We are moving forward.

I’ve been thinking about this for weeks. I used to think the U.S. was just ‘expensive’. But now I see it’s a two-tier system. One for the rich with brand-name drugs. One for the rest of us with generics. And the system is designed to keep it that way. The fact that Medicare is only negotiating 10 drugs? That’s not reform. That’s a distraction. They want us to think it’s getting better. It’s not. It’s just quieter.

The fact that Japan has the lowest prices isn’t because they’re cheap. It’s because they’re ruthless. Every two years, they say ‘this drug is too expensive’ and cut it in half. No drama. No lobbyists. Just math. The U.S. could do this. We just don’t want to.

I work in a pharmacy and I can tell you - the list price is a lie. Most people never pay it. But the ones who do? They’re uninsured. Or on Medicare with the donut hole. Or they’re on a plan that doesn’t cover it. And yeah, generics? We sell a ton. People are smart. They ask for the $4 version. But when they need something new? They’re screwed. The system is a maze. And the exit is always closed.