When a life-saving medication disappears from the pharmacy shelf, patients don’t just lose a pill-they lose stability, trust, and sometimes hope. Drug shortages aren’t rare anomalies anymore. In the U.S. alone, nearly 300 medications were in short supply in mid-2023, with heart drugs and cancer treatments among the most affected. But the real crisis isn’t just the lack of pills-it’s the silence that follows. Too often, patients find out about a shortage when their refill is denied, with no explanation, no plan, and no reassurance. That’s not just poor service. It’s a breach of care.

What Providers Are Responsible For

Healthcare providers aren’t just expected to prescribe medications-they’re responsible for guiding patients through every disruption. When a drug runs out, the job doesn’t end at calling the pharmacy. It starts with communication. The Joint Commission now requires providers to have structured, empathetic communication processes in place by January 2025. Non-compliance could mean losing accreditation. This isn’t bureaucracy-it’s basic ethics.Providers must tell patients before they notice something’s wrong. Waiting until the patient shows up at the pharmacy, confused and anxious, is too late. Proactive communication reduces anxiety by 41%, according to the American Medical Association. That means calling or sending a secure message the moment a shortage is confirmed-not when it’s too late to act.

What to Say: The Four Essentials

Patients don’t need jargon. They need clarity. The European Medicines Agency’s 2022 guidelines spell out exactly what information must be shared:- Which drug is affected (brand and generic name, strength, form-like 10mg tablet)

- How bad the shortage is (e.g., “Only 30% of normal supply is available”)

- When it might return (even an estimate helps: “We expect restock by late February”)

- What to use instead (and why it’s safe and effective)

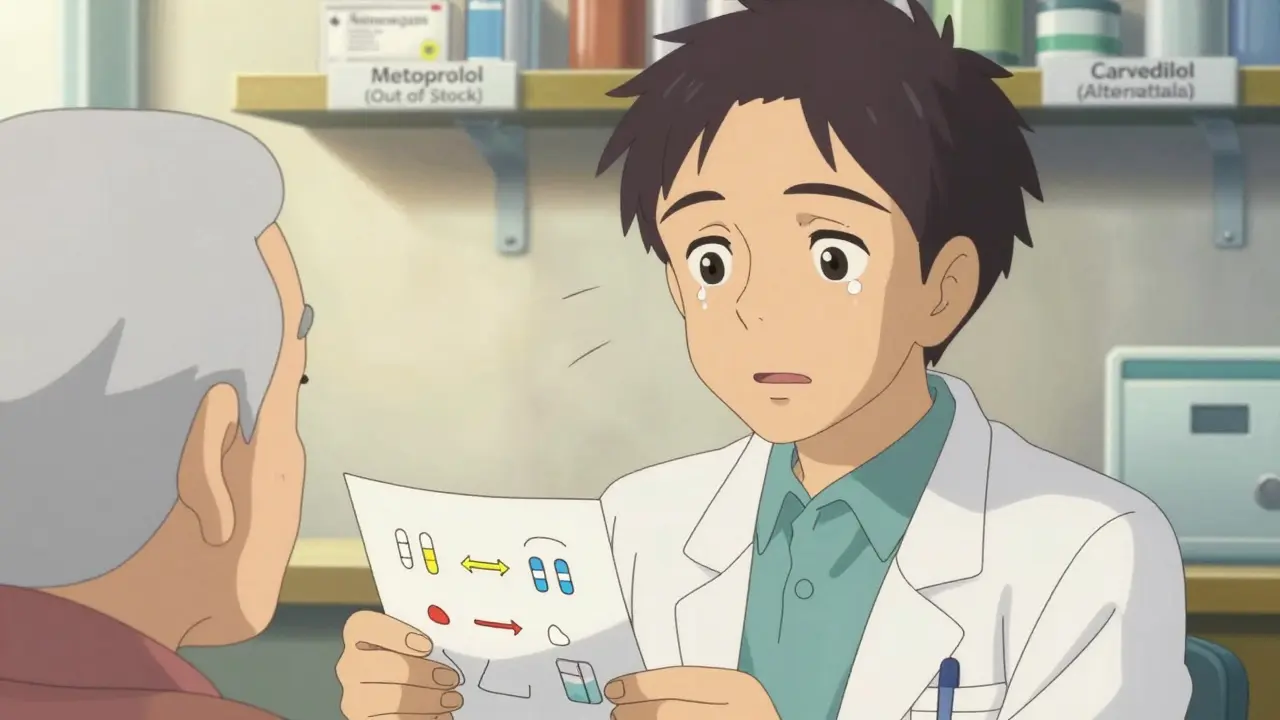

It’s not enough to say, “We’re switching you to this.” Patients need to understand why. For example: “Your old medication, metoprolol, is hard to get right now. The alternative, carvedilol, works similarly but also helps reduce fluid buildup. Studies show it’s just as effective for your blood pressure.”

And never assume they know the difference between generics and brands. A patient might think “carvedilol” is a completely new drug, not a replacement. Use plain language. Keep it at a 6th- to 8th-grade reading level. No acronyms. No Latin terms. If you wouldn’t say it to a family member, don’t say it to a patient.

How to Check If They Understand

Saying it isn’t enough. You have to make sure they heard it. The CDC’s “Chunk, Check, Change” method works: break information into small pieces, pause, and ask them to explain it back in their own words. This is called the teach-back method.Try this: “Can you tell me how you’ll take this new pill and why we’re switching?” If they say, “I take it when I feel dizzy,” that’s a red flag. They didn’t get it. Adjust. Repeat. Use visuals-simple charts comparing old and new meds, showing dosages and frequencies. A 2022 survey found that 19% of patients who received visual aids felt more confident about the change.

Don’t rush. The average doctor visit lasts just over 15 minutes. But a shortage discussion needs time. Kaiser Permanente solved this by embedding shortage alerts into routine visit workflows. Instead of adding 10 minutes, they added 2.7 minutes-because the conversation was planned, not rushed.

What Happens When You Don’t Communicate

Patients who aren’t warned report feeling abandoned. On Reddit, one user wrote: “My heart medication vanished. My doctor never said a word. I panicked, skipped doses, and ended up in the ER.” That story isn’t rare. In Healthgrades reviews, patients give clinics with poor shortage communication an average of 2.1 stars-nearly half the rating of clinics that handle it well.And it’s not just about feelings. When patients don’t understand why they’re switched to a new drug, they’re more likely to stop taking it. ASHP data shows that with poor communication, treatment discontinuation jumps to over 20%. With clear, empathetic explanations, it drops below 5%.

Worse, 63% of patients don’t ask questions during these conversations-even if they’re confused. A 2023 JAMA study found patients fear sounding ignorant or challenging their provider. That’s why providers need to invite questions: “What worries you most about this change?” not “Do you have any questions?”

Special Challenges: Rural and Non-English Patients

The gap in communication isn’t equal. In rural areas, 68% of providers say they don’t have real-time access to shortage updates. A patient in a small town might wait days to find out their insulin is unavailable-while someone in a big city gets a text alert within hours.For non-English speakers, the risk is even higher. Research shows they’re 3.2 times more likely to misunderstand shortage information. Translation apps aren’t enough. You need trained medical interpreters-not family members. And materials must be translated into the most common languages in your patient population. A Spanish-language handout on heart medication alternatives isn’t optional-it’s a safety issue.

What Works: Real Examples

Some clinics are getting it right. The Mayo Clinic’s SHIP protocol (Shortage Handling and Information Protocol) includes automated alerts, pre-written patient letters, and staff training. Their patient satisfaction with shortage communication? 87%. Compare that to clinics without protocols: just 54%.Memorial Sloan Kettering assigns trained communication specialists to handle all cancer drug shortages. These aren’t nurses or pharmacists-they’re professionals trained in trauma-informed communication. They spend extra time listening, answering fears, and connecting patients to support services. The result? Higher adherence, fewer panic calls, and less emotional distress.

Intermountain Healthcare built an EHR template that auto-fills shortage details into patient notes. When a provider selects a drug that’s in short supply, the system pulls in the alternative options, dosing info, and patient handouts. No typing. No forgetting. Just seamless, accurate communication.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a big budget or fancy software to start improving. Here’s what you can do right now:- Check your drug inventory weekly-don’t wait for patients to complain. Use the FDA’s Drug Shortages database or your pharmacy’s alert system.

- Create a simple one-page handout for common shortages: drug name, alternative, dose, why it’s safe, and contact info.

- Train your staff-even 30 minutes on teach-back and plain language makes a difference.

- Start proactive messaging-if you know a drug is running low, send a secure message to patients on that med before their next refill.

- Document everything-what you said, how they responded, what they understood. This protects you and the patient.

These aren’t extra tasks. They’re part of care. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation study found clinics with good shortage communication had 23% lower patient churn. People stay with providers who treat them like partners-not afterthoughts.

The Future Is Clear

By 2027, the market for shortage communication tools will be worth over $300 million. AI systems will predict shortages before they happen. The International Pharmaceutical Federation is developing global templates for patient communication. These tools will help-but they won’t replace human connection.Patients don’t need perfect systems. They need to know someone cares enough to tell them the truth, explain the change, and listen to their fears. That’s the responsibility. That’s the standard. And it’s not coming soon-it’s already here.

Been using the FDA shortage tracker for a year now and it’s saved my practice from at least three patient meltdowns

Just set up a weekly alert and stick it on your calendar. No fancy software needed. You’d be shocked how many docs still don’t check.

In rural India we face this daily. Insulin shortages hit harder because pharmacies don’t even know when the next shipment’s coming. We handwrite lists for patients: drug names, alternatives, where to get them next week. No tech, just paper and persistence.

It’s not glamorous but it keeps people alive.

THIS. I’ve been screaming this from the rooftops for years. Patients aren’t dumb they’re scared. And if you don’t tell them the truth they’ll Google it and come in convinced they’re dying from a pill swap. 🙏

Oh my god I’m so glad someone finally said this. My mom got switched from metoprolol to carvedilol and no one told her why. She thought it was a new cancer drug. She cried for three days. I had to Google it myself. This is medical malpractice. 😭

Let’s be real. Most clinics don’t care. They’re billing codes and KPIs. The Joint Commission’s new rule? Just another box to tick. Providers will send a templated email and call it good. No one’s actually teaching back or checking understanding. This whole thing is performative compassion.

I get where Alana’s coming from but I’ve seen clinics that actually do this right. One nurse I worked with would sit with patients for 10 minutes after a shortage alert. She’d draw pictures. She’d ask them what they were scared of. People cried. But they stayed on meds.

It’s not about the system. It’s about the person.

You think this is bad? Try being a provider in a state that won’t fund interpreter services. You’re forced to use Google Translate for a patient on warfarin during a shortage. One wrong decimal point and they bleed out. This isn’t just communication-it’s a liability crisis. And nobody’s holding the system accountable.

Stop praising the ‘good clinics.’ Fix the infrastructure.

Let me clarify something for the uninitiated: The Joint Commission’s mandate is not ‘ethical’-it is a regulatory necessity driven by malpractice litigation trends post-2020. The 41% anxiety reduction statistic cited? Derived from a single-center study with n=127. The 87% satisfaction rate at Mayo? Confounded by selection bias. The real issue is not communication-it is systemic underfunding of pharmaceutical supply chains. Until Congress allocates $2B to domestic API production, all this ‘empathy training’ is performative neoliberalism.

What happens when the alternative drug is also in shortage? I’ve seen cases where both metoprolol and carvedilol are unavailable. No one talks about that. What’s the backup? And what if the patient can’t afford the alternative? The article assumes access. Reality doesn’t.

The teach-back method is empirically sound-but only if the provider has the cognitive bandwidth to execute it. In a 15-minute visit with 12 patients, three emergencies, and an EHR that crashes every 10 minutes, ‘chunk, check, change’ becomes ‘say it fast, hope they nod, move on.’

It’s not that providers are uncaring-it’s that the system is designed to make care impossible. We’re asking surgeons to perform open-heart surgery with butter knives and duct tape. And then blaming them when the patient dies.

I used to be the nurse who just handed out the paper. Then I met a woman who skipped her heart meds for six weeks because she thought the new pill was poison. She almost died. Now I sit with every patient. I ask them to draw the pill. I let them cry. I don’t fix the shortage. But I don’t let them feel alone in it.

That’s the only thing that matters.