Every time you take a pill, get a vaccine, or use a new medicine, there’s a quiet global system working behind the scenes to make sure it’s safe. This isn’t science fiction-it’s pharmacovigilance, the science of tracking drug side effects across borders. And it’s more critical today than ever.

How the World Tracks Dangerous Drugs

The global drug safety system started in 1968, after the World Health Organization realized that drug side effects don’t wait for national borders. A medicine that causes liver damage in Brazil might also harm someone in India or Sweden-but without shared data, no one would know. So they built VigiBase, a central database managed by the Uppsala Monitoring Centre in Sweden. Today, it holds over 35 million reports of adverse reactions from more than 170 countries.

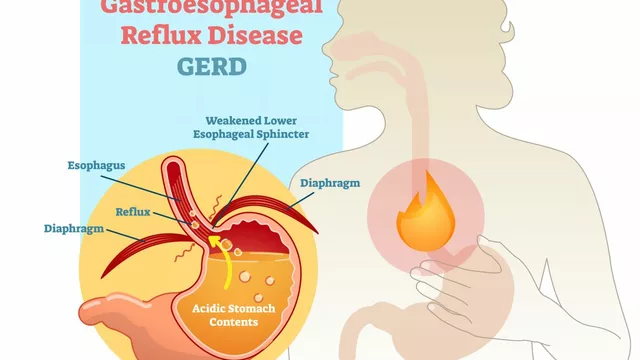

These reports aren’t random. They come from doctors, pharmacists, patients, and hospitals. Each one is an Individual Case Safety Report (ICSR), filled out with details like the drug name, the reaction (like a rash, heart issue, or liver failure), and when it happened. To make sense of millions of reports, everyone uses the same language: MedDRA, a medical dictionary with over 78,000 terms for symptoms. And drugs are labeled using WHODrug Global, which includes more than 300,000 medicine names across 60+ categories.

This system doesn’t just store data-it finds patterns. If ten people in different countries report the same rare reaction to a new diabetes drug, the system flags it as a potential safety signal. That’s how they caught the link between Dengvaxia and severe dengue in people who’d never had the virus before-first spotted in the Philippines, then confirmed globally.

Who’s Running the System?

The WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring (PIDM) is the backbone. But it’s not a top-down agency. It’s a network. Each country has its own national pharmacovigilance center. Some, like the U.S. FDA, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Australia’s TGA, run advanced systems. Others, especially in low-income countries, struggle with basic tools.

There are 34 countries classified as “Full Members” that actively send data to VigiBase. The rest either send occasional reports or don’t send any at all. That creates a big gap. Just 16% of the world’s population lives in high-income countries-but they submit 85% of all reports. Sweden reports 1,200 adverse events per 100,000 people each year. Nigeria? Just 2.3 per 100,000. That doesn’t mean Nigerians don’t have side effects. It means they can’t report them.

Meanwhile, the EU runs EudraVigilance, a legally binding system. Companies must report side effects within 15 days. The FDA’s FAERS gets about 2 million reports a year but doesn’t automatically feed into VigiBase-though it does contribute manually. The WHO system is voluntary. It doesn’t force anyone to report. It just makes it easier to connect the dots when they do.

Why Some Systems Work Better Than Others

Not all countries have the same tools. In the UK, healthcare workers use a mobile app to report side effects in under 48 hours. In Ethiopia, before they adopted the PViMS system in 2020, it took 90 days just to get a report from a rural clinic to the capital. After PViMS, that dropped to 14 days. But even now, only 35% of health facilities in Ethiopia report regularly-because of poor internet, lack of training, or no electricity.

Training is another issue. WHO says pharmacovigilance officers need 40 hours of specialized training. In Southeast Asia, 68% have had less than 15. That means reports are incomplete, unclear, or never filed at all.

Europe’s advantage? Active surveillance. Instead of waiting for reports, they mine electronic health records from 150 million patients. That’s how they found a 37% increase in signal detection speed. The U.S. and EU can catch problems faster because they’re looking for them, not just waiting for someone to call in.

The Money and the Market

Pharmacovigilance isn’t cheap. The global market was worth $5.38 billion in 2022 and is expected to hit $13.17 billion by 2030. Why? Because regulators demand it. The top 50 pharmaceutical companies now have pharmacovigilance teams averaging 250 people each-up from 150 in 2018. If a drug causes harm and the company didn’t report it properly, they face fines, lawsuits, or even a global recall.

But money doesn’t reach everywhere. In 50 African countries studied, the average pharmacovigilance budget was just $0.02 per person. In high-income countries, it’s $1.20. That’s a 60-fold difference. Some low-income systems rely entirely on donor funding. When that funding ends, the system shuts down.

That’s why the WHO’s Global Benchmarking Tool shows only 28% of countries have a formal system at all. The rest? They’re flying blind.

How Technology Is Changing the Game

Artificial intelligence is now helping sift through millions of reports. UMC’s AI system cuts false alarms by 28%. Instead of human reviewers spending weeks on noise, they focus on real signals. That’s huge.

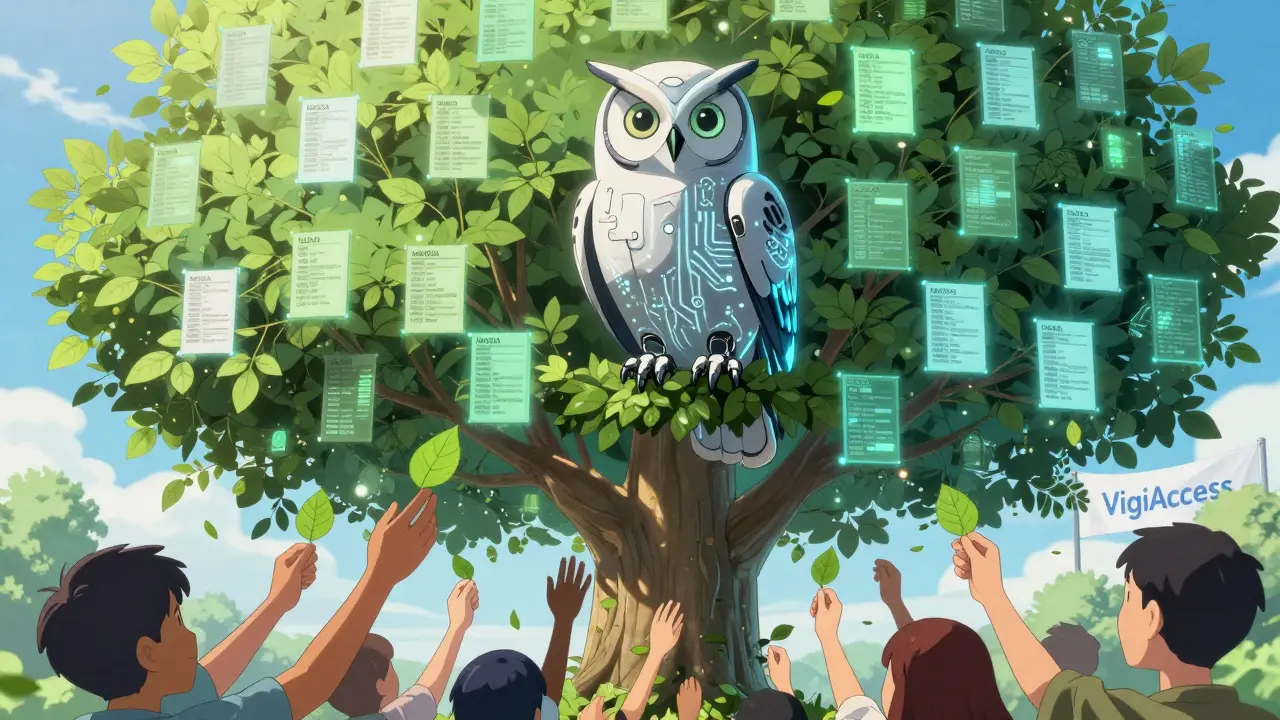

Another big change? Public access. Since 2015, anyone can use VigiAccess to search anonymized data from VigiBase. Doctors, researchers, even patients can look up what’s been reported about a drug. Over 12 million people have used it.

By 2025, the world will adopt ISO IDMP standards-100+ data elements that uniquely identify every medicine. Right now, “ibuprofen” might be listed as “Ibuprofen 200mg tablet,” “Ibu 200,” or “Advil” depending on the country. With IDMP, every version will be linked to one exact code. That means matching side effects across borders will be 40% more accurate.

What’s Still Broken

Even with all this tech and data, big problems remain. One is causality. When someone gets a headache after taking a new drug, was it the drug? Stress? Something else? The EU and U.S. agree on whether a case is drug-related only 63% of the time. That’s not good enough.

Another issue: reporting bias. If a drug is widely used in rich countries, side effects show up fast. But what about drugs used mostly in low-income countries? Like certain antimalarials or tuberculosis treatments? They’re often ignored until it’s too late.

And then there’s the political gap. When a drug is pulled in Europe but still sold in Africa, who decides? The WHO can recommend action-but it can’t force a country to act. That’s why experts like Dr. Maria P. G. Kaisermayer say we need an independent global review body for high-stakes safety issues.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. If you notice a strange side effect-rash, dizziness, nausea, unusual fatigue-report it. In many countries, you can file a report online or through an app. Even if you’re not sure, report it. One report might seem small. But 100 similar reports? That’s a signal.

And if you’re a patient in a low-income country, ask your pharmacist or clinic: “Do you report side effects?” If they don’t, push for it. Global safety starts with local action.

The Big Picture

International drug safety monitoring isn’t perfect. It’s uneven, underfunded, and slow in places. But it’s also the only reason we know about risks like Vioxx, thalidomide, or the Dengvaxia issue before millions more are harmed.

It’s the reason new drugs are safer today than ever before. It’s why you can trust that your flu shot won’t cause a rare nerve disorder. And it’s why, even with all the gaps, the world is slowly getting better at protecting you-from one report at a time.

So let me get this straight - we’ve got a global system that tracks drug reactions, but Nigeria reports 2.3 adverse events per 100k while Sweden does 1,200? That’s not a safety system, that’s a colonial data fantasy. If you’re not collecting reports from the Global South, you’re not monitoring safety - you’re just documenting the side effects of rich people’s prescriptions. And don’t even get me started on how ‘voluntary’ reporting is just a fancy way of saying ‘we don’t care if you die in a village with no internet.’

Let’s be honest - this entire system is a corporate theater. Big Pharma spends billions on pharmacovigilance not to protect you, but to check the box so they can keep selling drugs with known risks. The FDA’s FAERS database? A black hole. The WHO’s ‘voluntary’ network? A glorified suggestion box. And don’t pretend AI is fixing anything - it’s just filtering out the inconvenient truths so regulators can sleep at night. If you think this is safety, you’re the kind of person who believes the label on a bottle of aspirin.

Okay so let me ask you - when the WHO says ‘VigiBase has 35 million reports’ - who exactly is reporting? Are they really getting data from rural clinics in Ethiopia where the power goes out at 6 PM? Or is this just a numbers game cooked up by consultants in Stockholm who’ve never seen a malaria patient? And why does every ‘improvement’ like PViMS only help 35% of facilities? Because the other 65% are just collateral damage in the grand capitalist experiment. They don’t want you to know this, but your ‘safe’ flu shot was tested on people who never had a chance to say no. This isn’t science. It’s exploitation with a UI.

Reporting bias is real. But so is common sense. If you’re in a country with no infrastructure, don’t expect a system built for Berlin to work in Kinshasa. The problem isn’t the tech - it’s the assumption that one-size-fits-all.

The MedDRA terminology standardization is critical for signal detection. Without it, semantic interoperability between ICSRs would be statistically untenable. The WHODrug Global taxonomy enables precise pharmacological mapping across jurisdictions - a prerequisite for global pharmacovigilance. The ISO IDMP implementation in 2025 will further reduce ambiguity in drug identification, increasing causal attribution accuracy by an estimated 40%. Current limitations stem not from systemic failure, but from inconsistent adoption.

Oh please. The U.S. has 2 million reports a year and you’re acting like we’re the bad guys? Meanwhile, Europe has legal mandates and China barely reports at all. And now you want to blame the U.S. for global inequality? Get real. We pay for this system. We build the tools. We fund the WHO. If you can’t report, fix your own damn healthcare system instead of whining about ‘colonial data.’ We’re not your pharmacovigilance ATM.

I just took a new blood pressure med and got a weird tingling in my hands. I reported it on the app - took 3 minutes. I didn’t think it mattered, but now I feel like maybe it does? If even one person does this, it adds up. Also, if you’re in a low-income country and your clinic doesn’t report - ask them. Seriously. It’s not that hard. I’m not a doctor, but I know what my body feels like.

Hey everyone - if you’re reading this, please know that your voice matters. Even if you think your side effect is ‘just a headache’ - if others feel it too, it becomes a pattern. I’ve been on meds for 12 years and I’ve reported 7 different reactions. Some got ignored. One led to a warning label. You don’t need to be an expert. You just need to care enough to speak up. And if you’re in a country with no system? Start a local group. We’ve got tools. We’ve got networks. We’re not powerless. 💪

It is imperative to note that the absence of mandatory reporting obligations in the WHO system constitutes a structural deficiency in the global pharmacovigilance architecture. This non-binding framework undermines the principle of equitable public health protection.

While the article presents a superficially comprehensive overview, it conspicuously omits the ethical implications of leveraging low-income populations as passive data sources without equitable access to the resulting safety interventions. This is not pharmacovigilance - it is pharmaceutical surveillance with a humanitarian veneer.

Look - I get that this system’s messy. But think about it: without this network, we wouldn’t have known about Vioxx until thousands were already dead. We’re not perfect. But we’re trying. And every time someone reports a weird reaction, even if it’s just one person in a village with spotty Wi-Fi - that’s hope. That’s humanity. We’re not just tracking drugs. We’re tracking each other. And that’s kind of beautiful, honestly.

So let me get this straight - the WHO lets companies skip reporting for years, then acts shocked when people die? And you call this ‘safety’? This isn’t oversight - it’s a crime scene with a PowerPoint. Someone’s getting rich off dead people’s symptoms, and you’re praising the system? Wake up.

AI cutting false alarms by 28%? That’s great - but what if the real signals are being filtered out as ‘noise’? And who’s training the AI? Corporations? Governments? The same people who profit from the drugs? This isn’t progress - it’s automation of bias. And the fact that the U.S. and EU only agree on causality 63% of the time? That’s not science - that’s guesswork with a license.

So the rich countries report 85% of the data, and you’re surprised the poor countries get ignored? Newsflash: the system was designed to protect the wealthy. The rest are just noise. And now you want us to ‘report side effects’ like it’s a civic duty? Tell that to the mom in Lagos who can’t afford to miss a day’s work to fill out a form. This isn’t a safety net - it’s a class system with a database.