The TRIPS Agreement was meant to create fair trade rules for intellectual property - but for millions of people in low- and middle-income countries, it became a barrier to life-saving medicines. When it took effect in 1995, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) forced every World Trade Organization (WTO) member to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. Before TRIPS, countries like India and Brazil could make generic versions of drugs at a fraction of the cost. Afterward, those same drugs became unaffordable for governments and patients who couldn’t pay $10,000 a year for treatments that once cost $87.

How TRIPS Changed the Global Medicine Market

Before 1995, many countries didn’t patent medicines at all. India, for example, only protected the process of making a drug - not the drug itself. That allowed local manufacturers to reverse-engineer patented medicines and sell them as generics. A single course of HIV treatment that cost $12,000 in the U.S. could be bought for $60 in India. The World Health Organization estimated that generic drugs cost 5-10% of branded drug prices in those pre-TRIPS years.

TRIPS changed that. It required all WTO members to grant product patents on medicines. That meant no more copying. Even if a country had the capacity to produce a drug, it couldn’t legally do so without the patent holder’s permission. The result? A global spike in drug prices. By 2022, patented medicines made up 68% of the $1.42 trillion global pharmaceutical market - even though they accounted for only 12% of prescriptions. Meanwhile, in low-income countries, generics made up just 28% of prescriptions, compared to 89% in the U.S.

The Flexibility That Wasn’t Flexible Enough

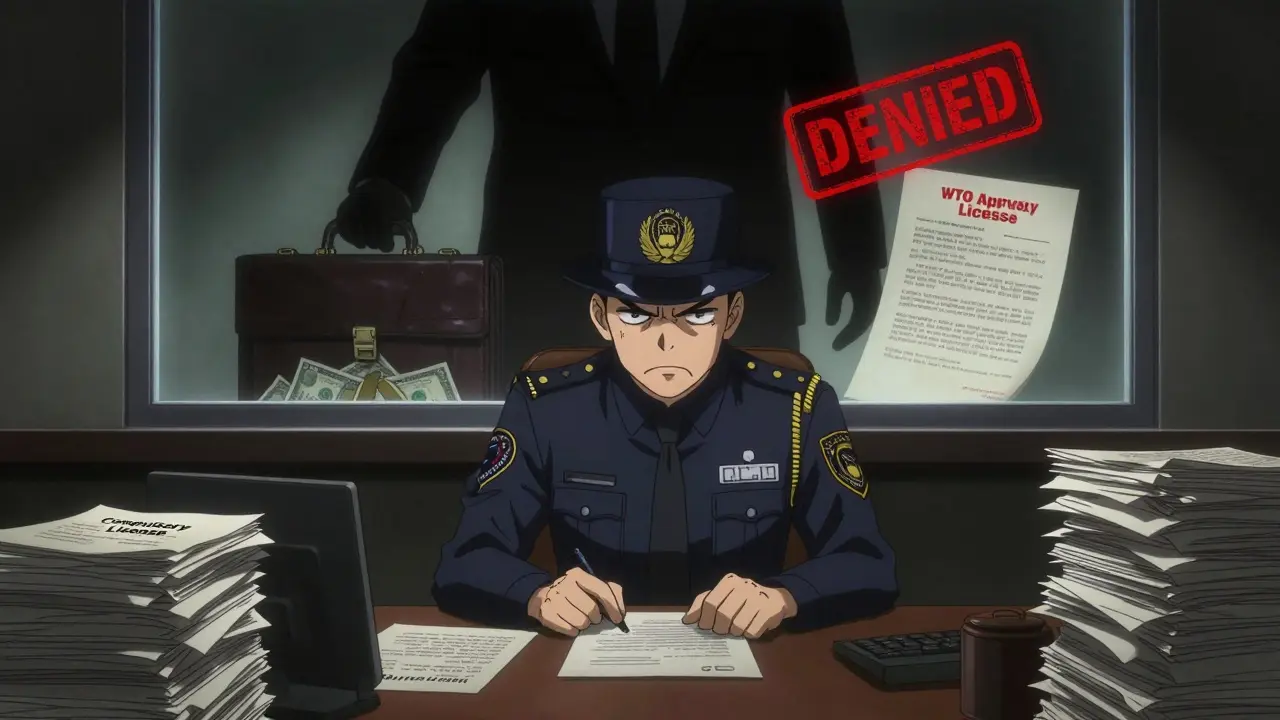

TRIPS wasn’t completely rigid. Article 31 lets countries issue compulsory licenses - meaning they can authorize generic production without the patent owner’s consent, usually during public health emergencies. The idea was simple: if a country can’t afford a drug, it can make or import a cheaper version.

But the rules came with strings attached. The original Article 31f said compulsory licenses could only be used for the domestic market. That crippled countries without drug factories. A nation like Rwanda, with no pharmaceutical industry, couldn’t legally import generics made in India - even if those drugs were cheaper and life-saving.

That’s why the 2005 Protocol Amendment (Article 31bis) was created. It allowed countries without manufacturing capacity to import generics made under compulsory license. Sounds fair, right? In practice, it was a nightmare. The system required 78 separate steps across two countries: notifications, legal filings, WTO approvals, export permits, and proof of need. The first and only time it was used? Rwanda in 2012, importing HIV medicine from Canada. It took four years. Médecins Sans Frontières called it “unworkable.”

Why Countries Don’t Use Their Own Legal Rights

Even when countries try to use compulsory licensing, they’re often scared off. Thailand issued licenses for HIV, heart disease, and cancer drugs between 2006 and 2008 - cutting prices by 30-80%. In response, the U.S. removed Thailand’s trade benefits, costing the country an estimated $57 million a year in lost exports. Brazil did the same with efavirenz in 2007, and the U.S. placed it on a “Priority Watch List” for two years.

A 2017 study of 105 low- and middle-income countries found that 83% had never issued a single compulsory license - not because they didn’t need to, but because they feared political and trade retaliation. The UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines documented 423 instances between 2007 and 2015 where wealthy nations threatened trade sanctions against countries even considering using TRIPS flexibilities.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and EU have pushed “TRIPS-plus” rules into bilateral trade deals. The 2011 U.S.-Jordan FTA, for example, extended patent terms beyond 20 years and blocked regulatory approval of generics until patents expired. These provisions have been added to 141 of the WTO’s 164 member states. Oxfam estimates they’ve cost LMICs $2.3 billion a year in lost savings from generic competition.

Voluntary Licensing: A Band-Aid on a Bullet Wound

The Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) was created as a softer alternative. It works by convincing pharmaceutical companies to voluntarily license their patents to generic manufacturers. As of 2022, MPP covered 44 patented medicines across HIV, hepatitis C, and COVID-19 - but only 1.2% of all patented drugs globally. And 73% of those licenses were restricted to sub-Saharan Africa, even though diseases like hepatitis C or diabetes affect people everywhere.

Voluntary licensing sounds good - until you realize it depends entirely on corporate goodwill. Companies choose which drugs to license, which countries to include, and when to pull out. They don’t have to. And when they don’t, there’s no enforcement. Compare that to Thailand’s 2006 move: it forced prices down by law. MPP’s approach helped some - but it didn’t fix the system.

The Real Cost of Inaction

Two billion people still lack regular access to essential medicines. In low-income countries, 80% of that gap is due to patent barriers. For HIV, cancer, diabetes, and heart disease, the difference between a generic and a branded drug can mean life or death. In South Africa, after the government finally moved to use TRIPS flexibilities in the early 2000s, HIV treatment costs dropped from $10,000 per patient per year to $87. That’s not a minor saving - it’s what allowed millions to survive.

And yet, 67 of the 48 least-developed countries still don’t have the legal tools to issue compulsory licenses - even though they’re granted until 2033 to catch up. Only 1.2 full-time staff members, on average, are assigned in these countries to handle intellectual property and medicine policy. There’s no one to fill out the forms, no one to fight the legal battles, no one to push back when the U.S. Trade Representative calls.

What’s Changing Now?

The pandemic forced a reckoning. In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a full TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. After two years of pressure, the WTO agreed - but only for vaccines. Therapeutics and diagnostics were left out. The waiver was narrow, delayed, and temporary. Still, it proved one thing: when enough countries demand change, the system can bend.

In September 2024, the UN High-Level Meeting on Pandemic Prevention adopted language calling for “reform of the TRIPS Agreement to ensure timely access to health technologies during health emergencies.” That’s not a promise - it’s a demand. The Access to Medicine Foundation’s 2023 Index shows that 7 of the top 10 drug companies now say they consider “human rights due diligence” - but only 14% of their patented medicines are covered by actual access plans.

The WHO’s 2023 Global Strategy on Digital Health even mentions TRIPS flexibilities as key to enabling local production of digital diagnostic tools - signaling that this isn’t just about pills anymore. It’s about vaccines, tests, therapies, and the next generation of health tech.

The Future Is Still Unclear

By 2030, the UN Development Programme projects that without major reform, medicine access gaps will affect 3.2 billion people. The current system is designed to protect corporate profits - not public health. Compulsory licensing works when used. The Rwanda case proved that. But it’s too slow, too complicated, and too risky for most countries to even try.

There’s no technical reason why generics can’t reach everyone. The science is there. The manufacturing capacity exists. The cost difference is undeniable. What’s missing is political will - and the courage to say that saving lives should come before patent rights.

What is the TRIPS Agreement?

The TRIPS Agreement, or Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, is a global treaty under the World Trade Organization (WTO) that sets minimum standards for protecting intellectual property, including patents on pharmaceuticals. It came into force on January 1, 1995, and requires all member countries to grant 20-year patents on medicines, limiting the production of generic versions.

Can countries make generic medicines under TRIPS?

Yes, but with major restrictions. Article 31 of TRIPS allows compulsory licensing - where a government authorizes a generic manufacturer to produce a drug without the patent holder’s permission, usually during a public health emergency. However, the original rule required these generics to be used only domestically. The 2005 amendment (Article 31bis) allows imports, but the process is so complex that it’s been used only once - by Rwanda in 2012.

Why don’t more countries use compulsory licensing?

Many countries avoid it due to fear of political or economic retaliation. Thailand lost $57 million in trade benefits after issuing licenses for HIV drugs. Brazil was placed on a U.S. watch list. A 2017 study found that 83% of low- and middle-income countries had never issued a single compulsory license - not because they didn’t need to, but because they were pressured not to.

What’s the difference between TRIPS and TRIPS-plus?

TRIPS sets the global minimum standard for patent protection. TRIPS-plus provisions are stricter rules added through bilateral trade deals - like extending patent terms beyond 20 years, blocking generic approval during patent life, or requiring data exclusivity. These are often pushed by the U.S. and EU and have been included in 86% of WTO member states, further limiting access to affordable medicines.

Did the COVID-19 TRIPS waiver help?

It helped a little - but not enough. In June 2022, the WTO approved a limited waiver covering only COVID-19 vaccines, not treatments or diagnostics. It was temporary, narrow, and didn’t change the underlying system. The waiver didn’t lead to a surge in generic production, partly because manufacturers still needed technology transfer and raw materials - which patent holders weren’t required to share.

What would real reform look like?

Real reform would remove patent barriers during public health emergencies, simplify compulsory licensing for imports, ban TRIPS-plus provisions in trade deals, and support local manufacturing in low-income countries. It would also require technology sharing - not just patent waivers - so that generics can be made faster and at scale. The goal: make medicine access a right, not a privilege.

Lmao this whole TRIPS thing is just Big Pharma’s way of keeping the poor dead. India made life-saving HIV drugs for $60 a year? Now they’re forced to charge $10k? That’s not trade policy, that’s genocide with a spreadsheet. And don’t even get me started on how the US threatened Thailand with trade sanctions just for trying to save its own people. We’re not talking about iPhones here - we’re talking about people who can’t breathe because they can’t afford the inhaler. This isn’t capitalism. This is feudalism with a patent lawyer.

You think this is about drugs? Nah. This is about control. The WHO, the WTO, the Gates Foundation - they’re all in bed with the same oligarchs who own the patents. That ‘compulsory license’ loophole? It’s a trap. They set it up so only countries with 12 lawyers and a NASA-grade bureaucracy can use it. Meanwhile, Rwanda took 4 YEARS to import one batch? That’s not a policy - that’s psychological warfare. And don’t believe for a second that the ‘COVID waiver’ was a win. It was a PR stunt. They let you make vaccines but not the syringes. The syringes are patented too. 😈

Bro. I work in pharma. I’ve seen the numbers. Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper - they’re just as good. The only reason brand names cost 100x is because they spend 90% of their budget on ads and lawyers, not R&D. That $12k HIV drug? The active ingredient costs $3. The rest is marketing, patents, and executive bonuses. We need to break the patent monopoly. Not ‘reform’ it - BREAK it. People are dying because we’re too scared to say: ‘profit shouldn’t come before life.’

I just want to say - I’ve read this entire post three times. And every time, I cry. Not because I’m emotional - but because I know what this means for real people. My cousin in rural Kenya? She’s on insulin. The brand version? $1,200 a month. The generic? $18. But the patent laws mean her clinic can’t legally import it. So she’s rationing. Skipping doses. Waiting. I don’t care about trade agreements. I care about my cousin. And if the system won’t protect her, then the system is broken. And it’s not just India or Rwanda - it’s every country that doesn’t have a seat at the table. We need to stop pretending this is about ‘fair trade’ and start calling it what it is: structural violence.

India made generics. Now we’re being punished for it. LOL. The West built its wealth on stealing tech - now they want to lock it down? Pathetic. If you think patents = innovation, you’ve never worked in a lab. Real innovation happens when you can build on what’s already there. We didn’t need 20-year monopolies to cure polio. We needed collaboration. Not corporate greed.

i just... i don't even know what to say anymore. i feel so helpless. like we're all just watching people die and saying 'well, it's complicated'... but it's not. it's simple. people need medicine. companies want profit. that's it. no more debates. just fix it.

Let’s be honest - this whole ‘TRIPS is unfair’ narrative is just Western guilt dressed up as activism. India has been ripping off patents for decades. We didn’t need TRIPS to protect us - we needed it to protect the world from Indian counterfeiters. The fact that you’re crying over ‘$60 HIV drugs’ while ignoring how India flooded the market with fake cancer meds? That’s hypocrisy. We don’t need ‘flexibility’ - we need enforcement. Real drugs. Real standards. Not cheap knockoffs that kill people.

why do people think the poor deserve free medicine? like... who pays for it? you? because i didn't sign up to fund your third world healthcare. if you can't afford it, don't take it. simple. the market works. if you want medicine, work for it. or move to a country that does. stop blaming corporations for being corporations. they're not here to be your charity

I love how people act like this is a new problem. Nah. This is the same story since the Industrial Revolution: power grabs disguised as progress. Patents were supposed to incentivize innovation - not create permanent monopolies. And now? We’re treating medicine like Apple AirPods. ‘Oh, you can’t afford the latest life-saving drug? Upgrade your bank account.’ 😂 We need to stop worshiping profit as a moral good. It’s not. It’s a tool. And right now, it’s being used to kill people. We need to change the game. Not just tweak the rules.

ok so i just read this and i have to say - i didn't know about the rwanda 4 year process?? that's insane. like, how is that even legal? and the whole 'threaten trade sanctions' thing?? we're literally punishing countries for trying to save lives?? i feel so ashamed. also i think the mpp thing is kinda cute but like... it's not a solution. it's a band-aid. we need to cut the whole leg off. like, why are we still having this conversation in 2024??

so let me get this straight - we’re okay with billionaires owning the patents on cancer drugs but we freak out when a country makes a generic? that’s not capitalism. that’s just… weird. also, the ‘TRIPS-plus’ stuff? that’s just corporate lobbying dressed up as diplomacy. it’s not policy - it’s extortion. and the fact that 83% of countries never issued a license? not because they didn’t need to - because they were scared? that’s not a system. that’s a cult.

i mean... i guess i see both sides? like, i get that people need medicine. but also... if you don't patent it, who's gonna invest in the next drug? innovation needs protection. maybe the solution isn't abolishing patents... just... making them more flexible? like... shorter terms? or tiered pricing? i don't know. i'm just tired. this feels too big.

As a public health professional from India, I must emphasize: the TRIPS Agreement was never intended to be a death sentence. The flexibilities exist - they are legally binding under international law. The failure is not in the text of the treaty, but in the political cowardice of low- and middle-income governments. We have the technical capacity. We have the manufacturing infrastructure. What we lack is the political will to confront powerful lobbies. The solution is not to dismantle TRIPS - it is to empower national institutions to enforce their own rights. We must stop waiting for permission. We must start exercising sovereignty. The time for silence is over.