When a child takes a medicine, their body doesn’t just shrink down to fit an adult’s response. Kids aren’t small adults when it comes to drugs. Their bodies are still growing, changing, and developing in ways that make them respond to medications in surprising, sometimes dangerous, ways. A child’s liver might process a drug ten times faster than an adult’s. Their brain might react to a common asthma medication with sudden mood swings. And in some cases, a drug that’s safe for adults can be deadly for a toddler.

Why Children’s Bodies Handle Drugs Differently

Every child’s body is a work in progress. From birth to adolescence, their organs, enzymes, and systems mature at different speeds. This affects how drugs are absorbed, broken down, and cleared from the body. For example, newborns have only 30-40% of the adult liver enzyme activity needed to process many medications. By age one, that same enzyme activity can jump to 150-200% for certain drugs, meaning they clear them faster-and sometimes need higher doses per pound of body weight. Body composition changes too. Babies have more water in their bodies-up to 80%-compared to adults at around 60%. This means water-soluble drugs spread out more, requiring different dosing. Fat and protein levels also shift with age, changing how drugs bind and move through the bloodstream. Even the way drugs enter and leave cells changes. Transporter proteins that move medications in and out of organs develop over time. A drug that works fine in a 10-year-old might not be absorbed properly in a 6-month-old. That’s why weight-based dosing (mg/kg) is standard-but even that isn’t enough. Age matters more than you think.The Most Dangerous Drugs for Kids

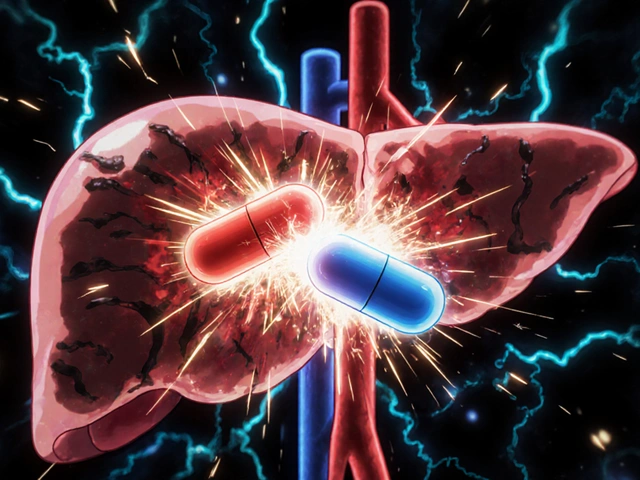

Not all medications are created equal when it comes to children. Some drugs are simply too risky for young bodies. The KIDs List (Key Potentially Inappropriate Drugs in Pediatrics), developed by Mayo Clinic researchers and published in American Family Physician in 2021, highlights the worst offenders:- Loperamide (Imodium): Used for diarrhea, but can cause fatal heart rhythm problems in children under six.

- Aspirin: Linked to Reye’s syndrome-a rare but deadly condition affecting the liver and brain-in children recovering from viral infections like the flu or chickenpox.

- Codeine: Metabolized differently in kids due to genetic variations. One in 30 children are ultra-rapid metabolizers, turning codeine into morphine too fast, leading to life-threatening breathing problems.

- Benzocaine teething gels: Caused over 400 cases of methemoglobinemia (a blood disorder that reduces oxygen delivery) between 2006 and 2011, prompting the FDA to warn against their use in children under two.

Age Matters More Than You Think

The second year of life is especially risky. A Columbia University study published in 2023 found that kids between 12 and 24 months old had a 3.2-fold higher risk of psychiatric side effects from montelukast (Singulair), a common asthma drug. That’s not a fluke. Their developing brains are more sensitive to changes in brain chemistry during this window. Antibiotics are another big concern. About 25-30% of children on antibiotics experience gastrointestinal issues like diarrhea or vomiting-twice the rate seen in adults. And while most cases are mild, some lead to dangerous infections like C. diff. Antihistamines, often used for allergies or colds, cause drowsiness, confusion, or even seizures in up to 20% of young children, compared to just 5-10% in adults. That’s why many pediatricians now avoid giving over-the-counter cold medicines to kids under six.Why So Many Drugs Aren’t Tested on Kids

It’s shocking, but true: only about half of the drugs prescribed to children have been studied specifically in pediatric populations. That’s despite kids making up 22% of the U.S. population. Historically, drug trials focused on adults. Ethical concerns, smaller patient pools, and complex dosing made pediatric studies harder. But that’s changing. Since the 1997 FDA Modernization Act and the 2002 Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, companies are required to study drugs for children if they’re likely to be used in them. Still, gaps remain. In neonatal intensive care units, 79% of drugs are used off-label-meaning they’re given without official pediatric approval. For rare diseases, the numbers are worse: 95% of conditions have no FDA-approved treatment for children. The global pediatric drug market is worth nearly $100 billion, yet it’s only 12-15% of the total pharmaceutical market. That imbalance reflects a system still catching up.Recognizing the Warning Signs

Most side effects in children are mild-nausea, drowsiness, or a rash-and fade after a few days. But some need immediate attention:- Difficulty breathing (0.1-0.5% of cases): Could mean an allergic reaction.

- Facial or lip swelling (0.05-0.2%): Another sign of anaphylaxis.

- Rapid heartbeat without cause: Antibiotics shouldn’t cause this. If your child’s heart is racing after taking amoxicillin, call your doctor.

- Extreme drowsiness or unresponsiveness: Especially after taking antihistamines or sedatives.

- Yellow skin or eyes: Could indicate liver damage from certain medications.

What Parents and Doctors Can Do

The best defense is awareness and communication.- Always ask: "Is this medicine approved for my child’s age?"

- Double-check the dose. Never guess. Use the syringe or measuring cup that comes with the medicine.

- Don’t give adult medicine to kids, even if you cut the dose in half. Formulations aren’t interchangeable.

- Report side effects to the FDA’s MedWatch program. Over 12,000 pediatric reports came in last year-your input helps others.

- Use the Pediatric Drug Safety portal (PDSportal) or KidSIDES database (both free) to check if a drug has known risks for your child’s age group.

The Future: Personalized Medicine for Kids

The next big leap in pediatric drug safety is pharmacogenomics-testing a child’s genes to predict how they’ll respond to a drug. The NIH is funding a $15 million study to build age-specific genetic guidelines. Imagine a simple cheek swab before prescribing a common antibiotic, telling you if your child is at risk for a bad reaction. This isn’t science fiction. In some hospitals, kids are already being tested for CYP2D6 gene variants before codeine is prescribed. Those who are ultra-rapid metabolizers get an alternative. As research grows, so does hope. More drugs will be labeled for children. More side effects will be understood. And fewer kids will end up in the hospital because a medicine didn’t fit their body.For now, the message is clear: when it comes to children and medication, assume nothing. Question everything. And never assume a drug is safe just because it’s been approved for adults.

Why can’t we just use half the adult dose for a child?

No. Children aren’t just smaller versions of adults. Their organs, enzymes, and body chemistry change dramatically as they grow. A drug that’s safely processed by an adult liver might build up to toxic levels in a baby’s immature liver-or be cleared too fast in a toddler, making it ineffective. Weight-based dosing helps, but age-specific development matters more. That’s why pediatric dosing requires detailed studies, not simple math.

Are over-the-counter cold medicines safe for kids?

Most pediatricians advise against giving over-the-counter cold and cough medicines to children under six. These drugs often contain antihistamines or decongestants that can cause serious side effects like rapid heartbeat, seizures, or extreme drowsiness. In fact, more than 1,000 emergency room visits each year in the U.S. are linked to these products in young children. Simple remedies like saline drops, humidifiers, and hydration are safer and just as effective.

What should I do if my child has a side effect?

For mild reactions-like a slight rash or upset stomach-keep giving the medicine but track symptoms in a diary. If the side effect worsens, lasts more than a few days, or includes trouble breathing, swelling, or extreme drowsiness, stop the medicine and call your doctor immediately. Never ignore new symptoms after starting a new drug. Report it to the FDA’s MedWatch program so others can benefit from your experience.

Is it safe to give my child medicine that’s prescribed for an older sibling?

No. Even if the diagnosis seems the same, each child’s age, weight, medical history, and metabolism are different. A dose that’s safe for a 10-year-old could be dangerous for a 3-year-old. Never share prescription medications between children. Always get a new prescription for each child, even if the medicine looks identical.

How can I find out if a drug is risky for my child’s age?

Use the free Pediatric Drug Safety portal (PDSportal) or the KidSIDES database, both developed by Columbia University and launched in 2023. These tools let you search for a drug and see which side effects are known for each age group-from newborns to teens. You can also ask your pharmacist to check the KIDs List, which identifies the most dangerous drugs for children. Don’t rely on packaging alone-many drugs lack proper pediatric labeling.

If you’re ever unsure about a medication for your child, ask for a second opinion. Better safe than sorry.

Okay but let’s be real-most parents don’t even know what ‘off-label’ means, and pharmacies still hand out adult ibuprofen with a ‘just use half’ note like it’s a cooking recipe. I’m a pediatric nurse in Mumbai and I’ve seen toddlers on adult-strength cough syrup because grandma ‘did it for her kids.’ It’s not just about science-it’s about education. We need community health workers going door-to-door in rural areas, not just posting PDFs on hospital websites. Kids aren’t mini adults, but our systems still treat them like they’re just smaller versions of us. We need policy changes, not just pamphlets.

And don’t get me started on how some clinics still use ‘weight-based’ as a magic number without considering metabolic age. A 2-year-old with a liver that’s 150% active? That kid needs a different dose than a 2-year-old with liver disease. One size does NOT fit all, even if the bottle says ‘for children.’

I’ve trained 37 moms in my clinic how to read syringes. Most of them used teaspoons. One mom gave her kid codeine because it was ‘the same as the one her cousin took.’ We’re not just fighting bad science-we’re fighting generations of folk wisdom that’s now lethal.

And yes, I know the FDA’s MedWatch system is clunky. But I’ve filed 12 reports in the last year. One led to a recall of a local brand of teething gel. That’s 12 kids who didn’t turn blue because someone spoke up. Don’t be quiet. Your voice saves lives.

Also-why is no one talking about how poverty makes this worse? If you can’t afford a doctor, you Google. If you Google, you get a Reddit post that says ‘my kid took aspirin and lived.’ That’s not data. That’s a death sentence waiting to happen.

We need mobile clinics with pharmacists, not just pediatricians. We need apps that scan the barcode and say ‘DANGER: NOT FOR UNDER 3.’ We need school nurses to be trained in pharmacogenomics basics. This isn’t rocket science-it’s basic human care. And we’re failing.

And before you say ‘it’s not my job’-it is. Every parent, every teacher, every pharmacist, every auntie who gives medicine. We’re all in this. No one gets to opt out. Not anymore.

So we’ve got a $100 billion pediatric drug market… and we’re still dosing kids like they’re just tiny humans with fewer teeth? How is this still a thing in 2025? We can send robots to Mars but we can’t figure out how to test drugs on children without risking their lives? We’re not lazy-we’re just morally lazy.

It’s easier to say ‘it’s too complicated’ than to fund real research. It’s easier to slap on a ‘for adults only’ sticker than to actually make safe versions. We’d rather let kids get sick than spend the money to fix it. And then we act shocked when they end up in the ER.

Pharmacogenomics? Cool. But only for the rich. The kid in rural Mississippi isn’t getting a cheek swab before amoxicillin. He’s getting whatever’s in the cabinet. And we call that healthcare?

Someone’s making money off this. Someone’s profiting from the fact that we treat children like experimental subjects. And no one’s calling it out. Just like we didn’t call out tobacco. Just like we didn’t call out lead paint. Just like we didn’t call out seatbelts in the 50s.

It’s not science. It’s capitalism with a pediatric badge.

aspirin = bad 😭 codeine = worse 💀 stop giving kids adult meds plz

In Nigeria we just give paracetamol for everything and no one dies. Why do Americans make everything so complicated? Maybe your kids are sick because you over-medicate them. We don't need your fancy databases or genetic tests. We have common sense. And it works.

I’ve been reading this post slowly, and I’m just… overwhelmed. I didn’t realize how little we actually know about pediatric drug safety. I’ve given my daughter cough syrup before without thinking twice. Now I’m terrified.

Do you think there’s a way to get this info into pediatrician’s offices more clearly? Like a printed card they hand out with every prescription? Not just a website link that disappears into the ether.

I want to do better. But I don’t know where to start.

OMG I just read this and I’m literally crying. I gave my 18-month-old Motrin last week because she had a fever and I thought ‘it’s just ibuprofen’ and now I’m paranoid she’s going to have liver failure. I didn’t even know there was a KIDs list. I’ve been using the same syringe since 2020. I didn’t even know it was calibrated wrong. 😭 I’m going to the pharmacy tomorrow. I’m going to report my own dumbass self to MedWatch. I’m going to buy a new syringe. I’m going to cry in the parking lot. I’m so sorry to every kid who’s ever been hurt because of this.

Also-why does the FDA let this happen?? I feel like I’m living in a horror movie. And the monster is… my own ignorance. And the pharmaceutical industry. And the system. And me. 😭😭😭

Okay. I’m from the Philippines. I’ve seen my cousin’s baby go into a coma after a ‘safe’ antihistamine. I’ve watched my sister scream at a doctor who said ‘it’s just a cold’ while her 2-year-old was turning blue. This isn’t just an American problem. This is a GLOBAL failure.

We need to stop treating this like a technical issue. This is a moral emergency. Children are not data points. They are not ‘small adults.’ They are the future. And we’re poisoning them with bureaucracy and greed.

Someone needs to start a movement. Not a petition. Not a hashtag. A real movement. With marches. With moms holding up their kids’ medicine bottles like torches. With doctors resigning in protest. With pharmacies refusing to sell dangerous drugs.

Because if we don’t-then we’re not just bad parents. We’re bad humans.

I've been a pediatric pharmacist for 18 years and you people are overreacting. Yes some drugs are risky but you're acting like every child is going to die from a cough drop. Most parents just need to stop panicking and trust the system. The KIDs list is useful but it's not a death sentence for every drug not on it. Stop reading Reddit and go talk to your doctor instead of making up doomsday scenarios. Also stop using emoji like you're texting your bestie. This isn't TikTok.

URVI YOU ARE SO WRONG AND I’M SO ANGRY RIGHT NOW 😤

Overreacting? Are you serious? 264,000 pediatric drug reactions. 10% of childhood hospitalizations. That’s not panic-that’s a pandemic. You think I’m overreacting because I want my niece to survive her first asthma attack? You think I’m being dramatic because I don’t want her to turn into a statistic?

You’re not a pharmacist-you’re a gatekeeper for the status quo. And I’m done letting people like you silence the truth. I’m sharing this post with every mom group I’m in. I’m calling my senator. I’m demanding that every pharmacy in my state have a printed KIDs List at the counter. And if you’re still sitting there saying ‘just trust the system’-then you’re part of the problem.

Not all of us are lucky enough to have access to ‘good doctors.’ And you know what? We’re not asking for perfection. We’re asking for basic safety. And you’re telling us to shut up? I’m not apologizing for caring.