Health News: Clavulanate, Scabies Fomites, and Practical Tips

Short, useful updates make staying healthy easier. Two recent topics are worth your attention: clavulanate’s role in hospital infections and whether scabies mites can spread from surfaces. Both affect everyday choices—how we use antibiotics and how we handle laundry, bedding, or shared spaces.

Clavulanate in hospital-acquired infections

Clavulanate is a beta-lactamase inhibitor that’s often paired with amoxicillin to block bacterial enzymes that destroy antibiotics. In hospitals, that combo can restore activity against bacteria that would otherwise resist treatment. That matters for common hospital problems like pneumonia and some urinary or wound infections where resistant bugs show up.

But pairing drugs isn’t a free pass. Doctors usually pick these combinations after cultures or when resistance is likely. Using clavulanate-plus-antibiotic without clear reason can still fuel resistance and cause side effects—diarrhea and, rarely, liver test changes. If you’re a patient, ask why a specific antibiotic was chosen and whether cultures or susceptibility tests support it.

Hospital teams also balance broad coverage with stepping down to narrower drugs once test results arrive. That’s antibiotic stewardship: start the right drug when needed, then switch to the simplest effective option. Patients can help by sharing allergy history, recent antibiotic use, and any past drug reactions.

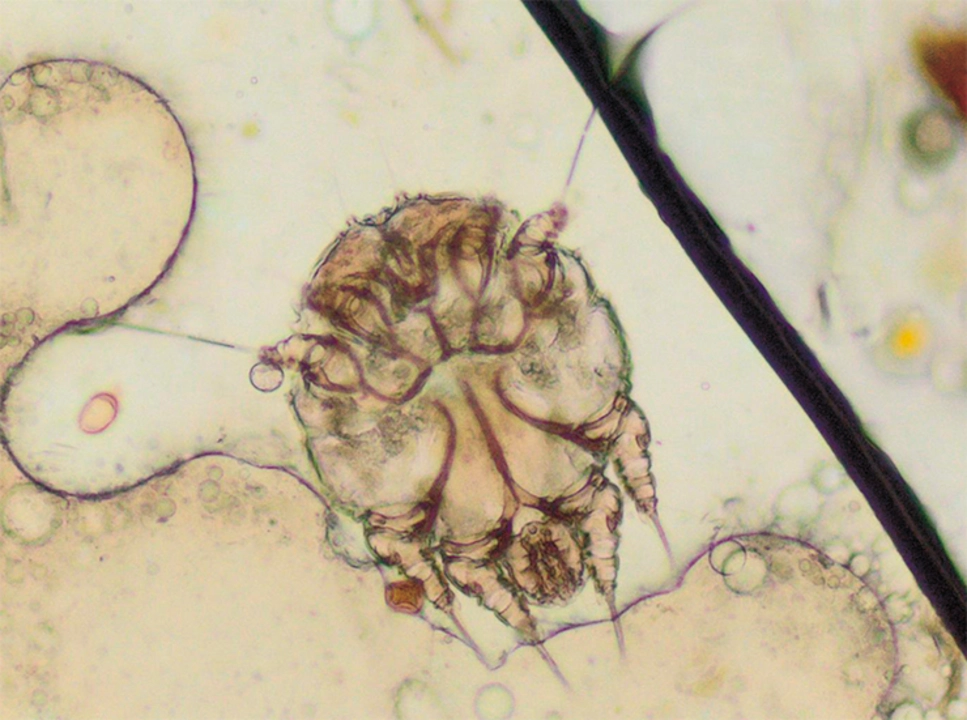

Scabies and fomite transmission: what to do

Sarcoptes scabiei, the mite behind scabies, spreads mainly through direct skin-to-skin contact. Still, mites can survive off the body for a limited time—studies and guidance commonly report survival up to about 72 hours on clothing, bedding, or furniture. That makes indirect transmission possible, especially in crowded settings or when items are shared within that window.

Practical steps are simple and effective. Wash clothes, sheets, and towels used by an affected person in hot water and dry on high heat. If washing isn’t possible, seal items in a plastic bag for three days so mites die. Vacuum furniture and carpets where close contact happened. Avoid sharing bedding or clothing until treatment is finished and items are cleaned.

Treating scabies quickly and treating close contacts prevents re-infestation. In dorms or care homes, coordinated cleaning and simultaneous treatment of roommates or residents helps stop outbreaks. If symptoms persist after treatment, follow up with a healthcare provider rather than repeating therapies without guidance.

Both topics show a common theme: small, specific actions—choosing antibiotics carefully, cleaning bedding promptly—have big effects. Ask questions, follow test results, and use clear, practical steps at home to reduce risk and speed recovery.

Recent Drug Safety Communications and Medication Recalls: What You Need to Know in 2025

Recent FDA drug safety alerts in 2025 include new opioid risk data, MRI requirements for Alzheimer's drugs, and warnings on ADHD and allergy meds. Know what's changed and what to do next.

The role of clavulanate in treating hospital-acquired infections

As a blogger, I've recently come across the significant role of clavulanate in treating hospital-acquired infections. Clavulanate is a powerful beta-lactamase inhibitor that is often combined with antibiotics like amoxicillin to increase their effectiveness against resistant bacteria. This combination helps to overcome the problem of antibiotic resistance in many hospital-acquired infections, including pneumonia and urinary tract infections. Additionally, clavulanate offers a broad-spectrum solution, effectively treating a wide variety of bacterial infections. It's truly fascinating how this mighty compound has become an essential weapon in our ongoing battle against antibiotic resistance in hospitals.

The potential for Sarcoptes scabiei to be transmitted through fomites

As a blogger, I've recently been researching the potential for Sarcoptes scabiei, the mite responsible for scabies, to be transmitted through fomites. From my findings, it's clear that these mites can indeed survive on various surfaces, such as clothing, bedding, and furniture, for up to 72 hours. This means that there's a potential risk of transmission through indirect contact with infested items, especially in crowded environments like dormitories or healthcare facilities. While direct skin-to-skin contact remains the primary mode of transmission, it's crucial to be aware of this secondary route and take appropriate precautions, such as regular cleaning and proper laundry management. In conclusion, it's important to be vigilant about both direct and indirect transmission of scabies to protect ourselves and others from this annoying and contagious skin condition.