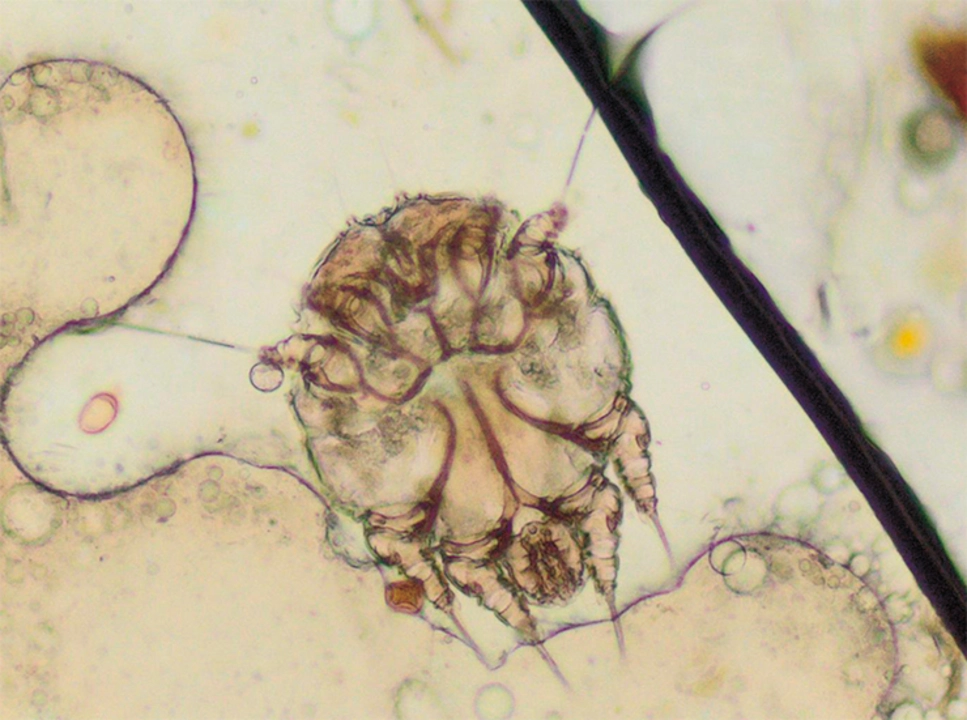

Understanding Sarcoptes scabiei and Fomites

Before diving into the potential for Sarcoptes scabiei to be transmitted through fomites, it is essential to understand what these terms mean. Sarcoptes scabiei, commonly known as scabies, is a microscopic mite that burrows into the skin, causing intense itching and rash. Fomites, on the other hand, refer to inanimate objects or materials that can carry and transmit infectious agents, such as bacteria or viruses. In this article, we will explore how scabies can be transmitted through fomites and the implications of this mode of transmission.

How Scabies is Typically Transmitted

Scabies is primarily transmitted through direct skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual. This close contact allows the mites to transfer from one person to another, where they can burrow into the skin and lay eggs. Transmission can also occur during sexual activity or when sharing personal items like bedding or clothing.

Investigating the Role of Fomites in Scabies Transmission

Although direct contact is the most common transmission route, several studies have investigated the potential for fomites to play a role in scabies transmission. These studies have often focused on the survival of the mites outside of their human host and their ability to infest new hosts from contaminated objects.

Survival of Scabies Mites on Fomites

Research has shown that scabies mites can survive on fomites for varying lengths of time, depending on factors such as temperature and humidity. Under optimal conditions, mites have been reported to survive for up to 2-3 days on fomites. This survival period may be shorter in hot and dry environments, as the mites are sensitive to desiccation.

Infestation from Contaminated Objects

Several case studies and anecdotal reports have suggested that scabies can be transmitted through fomites, particularly in settings where individuals share bedding or clothing. For example, outbreaks in institutions such as nursing homes or prisons have been attributed to the sharing of contaminated items. However, it is important to note that direct contact with an infected individual remains the most significant risk factor for scabies transmission.

Preventing Scabies Transmission through Fomites

While the risk of scabies transmission through fomites may be lower than through direct contact, it is still crucial to take steps to prevent the spread of the mites. Some preventive measures include:

- Regularly washing bedding, clothing, and towels in hot water and drying them on high heat

- Avoiding sharing personal items like brushes, combs, or hair accessories

- Sealing potentially contaminated items in plastic bags for at least 72 hours to kill any remaining mites

- Thoroughly vacuuming and cleaning living spaces, paying particular attention to areas where an infected individual has spent time

Diagnosing and Treating Scabies

If you suspect that you may have been exposed to scabies through fomites or direct contact, it is important to see a healthcare professional for diagnosis and treatment. Diagnosis is typically made based on clinical examination and patient history, and treatment usually involves the use of topical medications to kill the mites and alleviate symptoms. It is also important to treat household members and close contacts to prevent reinfection.

Understanding the Limitations of Current Research

While it is clear that scabies mites can survive on fomites and potentially infest new hosts, more research is needed to better understand the role of fomites in scabies transmission. Many studies on this topic have been limited by small sample sizes, varied methodologies, and a lack of standardization in mite survival assessments. Additionally, more research is needed to determine the relative importance of fomite transmission compared to direct contact in various settings.

Conclusion

Scabies is a highly contagious skin condition caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei mite. While direct skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual is the primary mode of transmission, there is evidence to suggest that fomites may also play a role in the spread of the mites. By understanding the potential for fomite transmission and taking appropriate preventive measures, we can help reduce the spread of scabies and improve the health and well-being of those affected by this condition.

Wow, this deep dive into scabies and fomites really shines a light on something many of us overlook. The way you broke down the mite’s survival timeline makes it crystal clear why a bit of extra laundry hygiene can be a game‑changer. I love how you highlighted both the direct skin contact and the less obvious fomite route – it gives us a fuller picture. For anyone dealing with an outbreak, those practical tips on washing and sealing items are pure gold. Keep spreading that knowledge; the more we know, the safer everyone feels.

Don't forget the shadow networks behind the scenes – they're feeding us misinformation about how "harmless" fomites are, all to keep us complacent.

Gather round, fellow truth‑seekers, for the scabies saga is far more twisted than the headlines let on. The mite, a tiny yet tenacious tyrant, can hunker down on your blankets like a covert operative, waiting for the perfect humidity to strike. Picture this: a warm, damp dorm room, a shared couch, a forgotten sweater – each a potential launchpad for a microscopic invasion. Scientists have documented mites surviving up to three days, but in the right (or wrong) conditions, that window can stretch like a dark summer night. The real horror isn’t the itch; it’s the silent, unseen hand that brushes against us in shared spaces, slipping the parasite into our lives like a whisper in a crowded hall.

Now, consider the institutional settings – nursing homes, prisons, shelters – where laundry cycles are rushed and privacy is a luxury. Those cramped quarters become breeding grounds, and the fomite route is no longer a footnote but a headline in a tragedy of neglect. Even the most diligent dermatologist can miss a case if they focus solely on skin‑to‑skin contact, ignoring the sinister role of contaminated linens and towels.

In the grand tapestry of public health, we must ask why funding for comprehensive fomite studies remains a ghostly afterthought. The pharmaceutical giants love a simple narrative: “apply cream, kill the bug.” They don’t need to fund the messy, expensive research into how mites survive on your couch cushions. And while we’re on the topic, let’s not forget the hidden agenda of manufacturers who push single‑use fabrics, creating a false sense of security while peddling profit.

Bottom line: treat every shared object as a potential carrier, not just a convenient accessory. Wash at 60°C, dry on high heat, and seal suspect items for at least 72 hours – these aren’t just recommendations, they’re armor against an invisible siege. The battle against scabies isn’t only on the skin; it’s waged on every pillowcase, every shirt, every stray sock that has ever brushed against an infected soul. Stay vigilant, stay informed, and remember: the smallest foe often requires the biggest vigilance.

Great points, Aimee! I’d add that regularly rotating and sun‑drying bedding can speed up mite death, since UV light is lethal to them. Also, using a steamer on upholstery adds a quick heat burst that’s hard for the mites to survive. For households with a confirmed case, it’s wise to launder all fabrics in hot water at once, not just the obvious ones. Don’t forget to vacuum carpets and then discard the bag outside to avoid re‑contamination. These extra steps, while a bit of work, can really tip the odds in our favor.

Fomites are the hidden villains of the scabies saga.