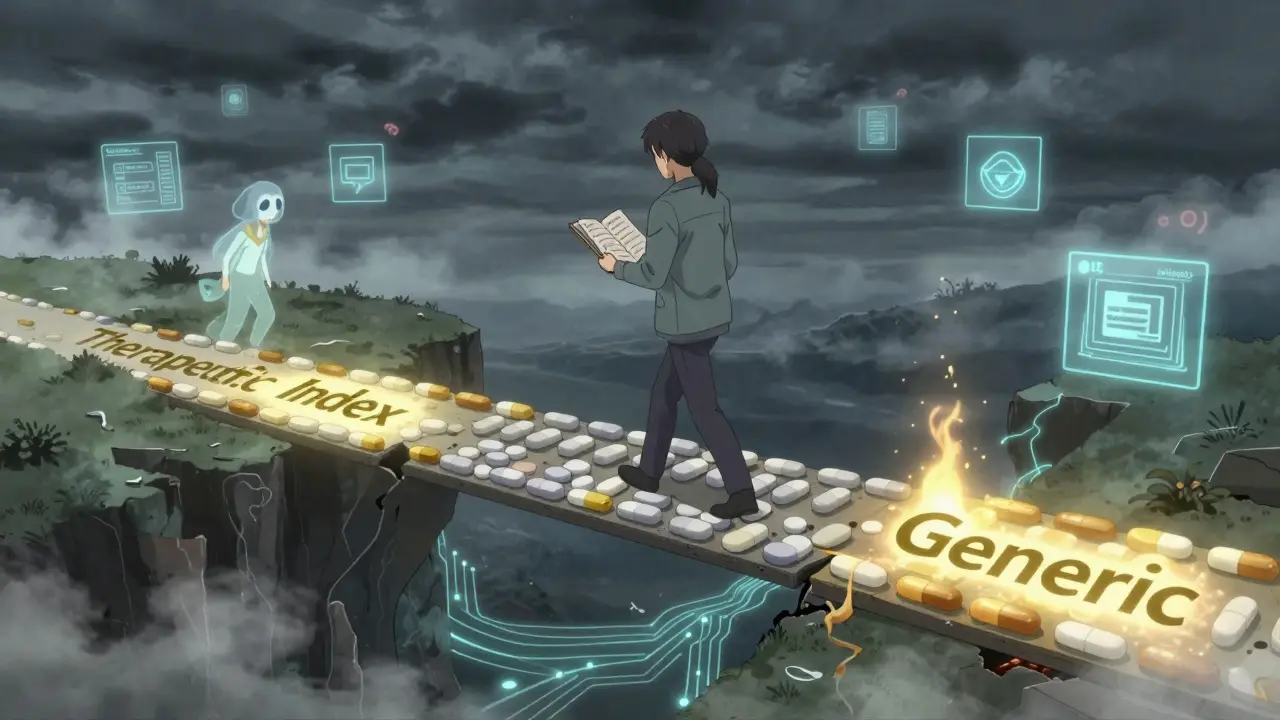

Switching from a brand-name drug to a generic version is supposed to save money without sacrificing results. But what happens when you or a loved one starts feeling different after the switch? Maybe the seizures are coming back. Or the blood pressure won’t stay down. Or you’re more tired than usual. These aren’t just "in your head"-they’re real signals that need attention.

Why a Generic Switch Can Change How You Feel

The FDA says generics must be bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That means the active ingredient must be the same, and it must get into your bloodstream at nearly the same rate and amount. The math? The amount of drug absorbed must fall within 80% to 125% of the brand’s levels. Sounds tight, right? But here’s the catch: that 45% range still allows for a big difference in how your body actually experiences the medicine. For most drugs-like lisinopril for blood pressure or atorvastatin for cholesterol-that range doesn’t matter much. Studies show no real difference in hospitalizations or outcomes between brand and generic versions. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), even small changes can be dangerous. These are medicines where the difference between working and causing harm is razor-thin. Think warfarin (blood thinner), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), digoxin (heart medication), and certain seizure drugs like phenytoin or carbamazepine. A 2019 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that patients switched from brand to generic digoxin had a 34.7% higher chance of being hospitalized for toxicity. Another study showed 23.4% of people switched from brand to generic levothyroxine had their TSH levels go out of range within six months, compared to just 8.2% of those who stayed on the brand. That’s not a fluke. That’s a pattern.What to Track: The 4 Key Signs Your Generic Isn’t Working

You don’t need a lab coat to spot trouble. Start by watching for these four red flags after your switch:- Changes in symptoms-If you had your seizures under control and now you’re having more, or if your depression symptoms are creeping back, that’s a major signal. On PatientsLikeMe, 64% of people with epilepsy reported more seizures after switching generics.

- Lab values shifting-For NTI drugs, your doctor should be checking specific numbers. If your INR for warfarin jumps from 2.4 to 3.8, or your TSH goes from 1.8 to 6.1, that’s not normal. These aren’t random fluctuations-they’re warnings.

- More ER visits or urgent care trips-The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative found a 12.3% increase in emergency department visits among patients switched to generic seizure drugs. If you’re going to urgent care more often, ask why.

- Stopping the medication-If you run out and don’t refill it for 90 days or more, that’s a strong sign you didn’t trust it. A 2018 study showed generic switchers were 18.7% more likely to discontinue than those who stayed on brand or authorized generics.

How Doctors and Pharmacies Should Be Tracking You

Good care doesn’t end at the pharmacy counter. The best practices for tracking effectiveness follow a clear timeline:- Before the switch: Document your baseline. What are your current lab numbers? What symptoms are you managing? Keep a journal-even a simple one on your phone.

- Days 1-7: Your pharmacist should call or message you. Ask: "How are you feeling? Any new side effects?" This isn’t optional. It’s standard in programs like Kaiser Permanente’s, which reduced adverse events by 42% with this step.

- Days 8-90: This is the critical window. For NTI drugs, labs should be checked weekly or every two weeks. For others, monthly is fine. If your doctor doesn’t schedule a follow-up, ask for one.

- Day 90+: If everything’s stable, you can return to normal monitoring. But if symptoms changed or labs drifted, you need to act.

When to Ask for Your Original Brand Back

Not every switch needs to be permanent. If you’re having problems, you have options:- Request a brand-name exception: Many insurance plans allow you to stay on the brand if your doctor documents medical necessity. You’ll need a note saying the generic caused issues.

- Ask for an authorized generic: These are made by the brand company but sold under a generic label. They’re identical to the brand-no changes in fillers or manufacturing. They’re often cheaper than the brand but just as reliable.

- Check the FDA’s Orange Book: Look up your drug. If it has an "AB" rating, it’s considered equivalent. If it’s "BX," that means there’s uncertainty. Don’t switch BX drugs without a clear plan.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to wait for your doctor to notice something’s off. Here’s your action plan:- Write down your symptoms before and after the switch. Be specific: "I had 2 seizures last month, now I’ve had 5." Or, "My heart was racing every night after the switch."

- Call your pharmacy and ask: "Was I switched to a generic? Which one?" Write down the name and manufacturer.

- Check your lab results from the last 3 months. Are your numbers moving? If so, bring them to your doctor.

- Request a follow-up appointment within 30 days. Say: "I was switched to a generic and want to make sure it’s working the same way."

- Ask about authorized generics or brand exceptions if you’re on an NTI drug.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In 2022, 90.1% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were generics. That’s huge savings-for insurers, for pharmacies, for you. But savings shouldn’t come at the cost of safety. The FDA’s new rules require post-marketing studies for all NTI generics approved after January 1, 2024. That means they’re finally taking this seriously. New tools are emerging too. Epic’s software now flags patients at risk based on age, kidney function, and other meds they take. AI models can predict with 83.7% accuracy who’s likely to have problems after a switch. But these tools won’t help if you don’t speak up. The truth? Most people don’t know they can ask to stay on a brand. Most doctors don’t know how to track it. Most pharmacists aren’t required to follow up. That’s why you have to be your own advocate.Real Stories, Real Results

One woman in Sydney switched from brand levothyroxine to a generic and started feeling exhausted, gaining weight, and having brain fog. Her TSH jumped from 2.1 to 8.9. She went back to her doctor, asked for the brand, and within six weeks, her symptoms vanished. Her TSH dropped back to 2.3. Another man on generic warfarin had two nosebleeds and a fall after his switch. His INR was 4.6-dangerously high. He switched back to the brand and has been stable for over a year. These aren’t rare cases. They’re common. And they’re preventable.If you’ve been switched to a generic and feel off-don’t assume it’s just "adjusting." Don’t wait for your doctor to notice. Track your symptoms. Check your labs. Ask for help. Your health isn’t a cost-saving experiment.

Can generic medications really be less effective than brand names?

Yes, for certain drugs-especially those with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI)-generics can lead to different outcomes. While the FDA requires generics to be bioequivalent, the allowed range (80-125% of brand absorption) can still cause noticeable changes in patients taking drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or seizure medications. Studies show higher rates of lab abnormalities, hospitalizations, and symptom recurrence after switching to generics in these cases.

How long should I wait before deciding if the generic is working?

For most medications, give it 30 to 90 days. But for NTI drugs like thyroid hormones or blood thinners, monitor closely within the first 14 days. Lab tests should be done at 7, 30, and 90 days post-switch. If symptoms worsen or labs shift significantly before 90 days, don’t wait-contact your doctor immediately.

What should I do if I think the generic isn’t working?

First, document your symptoms and any lab results. Then contact your doctor and pharmacist. Ask if you were switched to a generic and which one. Request a follow-up appointment. If you’re on an NTI drug, ask about switching back to the brand or an authorized generic. Insurance often allows exceptions if you provide medical documentation.

Are all generics the same?

No. Generics are required to have the same active ingredient, but they can differ in inactive ingredients (fillers, dyes, coatings) and how quickly they dissolve. These differences can affect absorption, especially in people with sensitive digestive systems or those taking multiple medications. The FDA rates generics with "AB" (equivalent) or "BX" (uncertain) codes-check the Orange Book for your drug’s rating.

Can I ask my pharmacist to give me the brand instead of a generic?

Yes, but you may need to pay more. You can ask for the brand-name drug by name, or ask for an "authorized generic"-which is made by the brand company but sold as a generic. Some insurance plans require a doctor’s note to cover the brand if a generic is available. Always ask your pharmacist: "Is there a brand or authorized generic option?"

What’s the difference between a generic and an authorized generic?

A regular generic is made by a different company using the same active ingredient but possibly different fillers or manufacturing processes. An authorized generic is made by the original brand company under a different label. It’s identical in every way to the brand-name drug-same ingredients, same factory, same quality control. It’s often cheaper than the brand and more reliable than a standard generic.

Why don’t doctors always monitor patients after a generic switch?

Many doctors assume bioequivalence means clinical equivalence. But that’s not always true. Time constraints, lack of automated alerts in electronic records, and lack of standardized protocols mean many patients fall through the cracks. Only 38.7% of U.S. hospitals have systems that flag lab changes after a switch. That’s why patient advocacy is critical-you can’t wait for the system to catch up.

Is there a way to know if my generic is high-risk before I take it?

Yes. Check the FDA’s Orange Book online or ask your pharmacist for the therapeutic equivalence code. If it’s "AB," it’s considered equivalent. If it’s "BX," there’s uncertainty about bioequivalence, and switching may carry higher risk. Also, if you’re taking a drug for epilepsy, thyroid disease, heart rhythm, or blood thinning, treat it as high-risk unless proven otherwise.

Been there. Switched to generic levothyroxine and felt like a zombie for three weeks. TSH went from 2.0 to 7.9. Called my pharmacy-turns out it was a different manufacturer. Switched back to brand, back to normal. Don’t let them treat your thyroid like a commodity.

This is one of those topics where the system fails patients because it’s easier to automate than to care. The FDA’s 80–125% bioequivalence range sounds scientific, but it’s a statistical loophole that ignores human biology. For drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, that range isn’t just acceptable-it’s dangerous. And yet, pharmacies still swap them without a second thought. We need mandatory patient counseling and lab follow-ups for NTI drugs. Not a suggestion. A requirement. Your life isn’t a cost center.

Ugh. I’m so tired of people acting like generics are ‘the same.’ My cousin switched to generic carbamazepine and had three grand mal seizures in a week. Her neurologist said ‘it’s probably just stress.’ No. It was the pill. She’s back on brand now and fine. Stop pretending chemistry is magic.

Great post! Really glad someone’s putting this out there. I’m from India and we use a lot of generics here-some good, some sketchy. But this reminds me: always check the maker, always track your symptoms. You’re not being paranoid-you’re being smart.

There’s a reason my doctor won’t switch me off brand for my seizure meds. I’ve had this since I was 16. I’ve tried generics twice. Both times, my EEG spiked. My neurologist says: ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’ And honestly? I’m not risking another hospital stay over a $10 savings.

Let’s be clear: the entire generic substitution paradigm is a regulatory farce. Bioequivalence is measured via Cmax and AUC, which are population-level metrics. But individual pharmacokinetics vary wildly due to gut flora, CYP450 polymorphisms, and even diurnal rhythm. You can’t reduce personalized medicine to a 45% absorption window and call it science. This isn’t just about drugs-it’s about the commodification of biology.

It’s not just about the pills-it’s about the silence. The system doesn’t want you to know you have a choice. Pharmacists aren’t trained to warn you. Doctors assume you’re fine unless you scream. And insurers? They’ll drop you if you ask for the brand. But here’s the truth: your body isn’t a spreadsheet. It’s not a line item. It’s your life. And if you feel different after a switch? You’re not imagining it. You’re being gaslit by a profit-driven machine. Speak up. Demand labs. Demand documentation. Demand your dignity.

Y’all are overreacting. The FDA wouldn’t approve generics if they were dangerous. This is just people who don’t understand science. I bet half of you are anti-vaxxers too. Stop being paranoid. It’s the same chemical. End of story.

While I appreciate the anecdotal evidence presented, one must recognize the inherent methodological limitations of self-reported symptomatology. The placebo effect, nocebo effect, and confirmation bias are rampant in patient narratives, particularly in the context of pharmacological substitution. The clinical trials underpinning bioequivalence are statistically robust and peer-reviewed-unlike the anecdotal reports circulating in online forums. To elevate individual experience above population-level pharmacokinetic data is to misunderstand the very foundation of evidence-based medicine.

Did you know the FDA doesn’t inspect generic factories the same way they inspect brand-name ones? And that 80% of generic pills are made in India and China, where quality control is a joke? They’re cutting corners with fillers that trigger autoimmune flares. This isn’t about savings-it’s about corporate collusion. The real drug companies own the generics too. They’re just hiding behind labels. You’re being experimented on. Wake up.

Look. I’m a pharmacist. I’ve seen this play out a hundred times. The problem isn’t the generic. It’s the patient who doesn’t follow up. You don’t get your labs checked. You don’t tell your doctor you feel weird. Then you blame the pill. Meanwhile, the brand-name company is spending millions on marketing to scare you into paying $300 for a pill that costs $3 to make. Stop being manipulated. If you’re on an NTI drug, get tested. But don’t let fear-mongering turn you into a pawn in Big Pharma’s game. The system’s broken? Fix it with data-not drama.